Sci-Fi: A History of Genre Bias

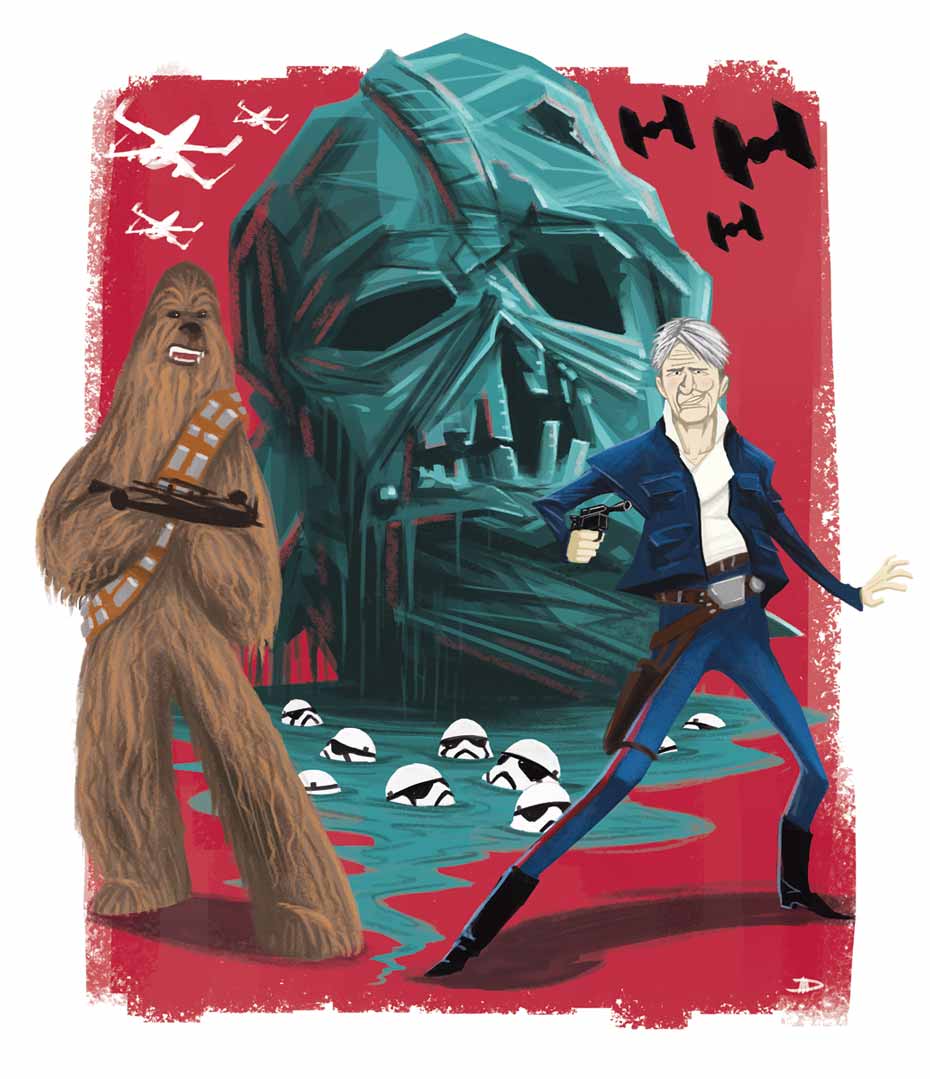

Right before Christmas, on December 18, the much anticipated release of Star Wars: Episode VII – The Force Awakens will hit theaters all across the United States heralding the return of the juggernaut that is the Star Wars franchise. Franchise life will continue as usual: McDonald’s will have happy meals with plastic droids inside them; children and adults alike will clamor to collect each new relevant piece of material both plastic and otherwise.

It will be the highest grossing film of 2015 and it will get little to no respect from the cinematic community. Let me explain why: Of the top 10 highest grossing films of all-time, five of them are in the sci-fi genre: Avatar, Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace, Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, ET, and The Hunger Games: Catching Fire. The Star Wars franchise alone has made close to $4.5 billion in worldwide box office sales since the release of the original Star Wars film in 1977, this means that the $461 million that Star Wars made at the box office would translate into an absurd $1.8 billion in revenue today.

What do these numbers mean? It means that people like sci-fi. And how many of these absurdly popular sci-fi movies won the Oscar for best picture? Zero. So, why is it that science fiction films don’t get the same respect that might be reserved for other genres? Will we ever see a time when people can look past spaceships and laser battles and see the fecund well of emotions that lie at the epicenter of so many of these films, and from which springs true works of art?

In the entire history of the Academy Awards, dating back to its inception in 1929, there have only been eight movies that have even been nominated for Best Picture that fall into the sci-fi genre. Not included on this list: 2001: A Space Odyssey, which can be found in the top 25 of just about every list of the greatest movies of all time.

It seems as though the Academy quantifies the quality of a film based on the personal connection that they share with the characters in the story. Even if you have never experienced first-hand the events that occur in the movie that you’re watching, one can understand that these events did happen and perhaps you know someone who participated in what you are watching, connecting you to the movie by proxy. For instance, in the film The Hurt Locker we follow the story of a young man in the army during the Iraq War who seems to become animated to the point of arousal diffusing bombs. Now, I have never been to Iraq nor have I participated in any type of warfare. I do, however, understand that these things do actually happen. The truth of the matter is that there really are people who defuse bombs, and some of them do this in Iraq. I cannot say, however, that I have ever fought a Stormtrooper, befriended an Ewok, or used the Force to persuade someone to let me through their gates. I don’t know anyone who has done these things and neither do you. This seems to be where the disconnect with actual human experience occurs and the perceived value of the movie declines in the eyes of the Academy.

It would seem that the average movie-goer enjoys being taken on a journey in which the only boundaries are found within the imagination of the storyteller. Here seems to be where the proof lies, and not just anecdotally that this is the case. Out of the top 10 grossing movies of all-time, nine of them tell stories about things that you have no relation to. You have never helped an alien “phone home,” you don’t know anyone who has ever been to Pandora, you have never had your city saved by a filthy rich guy who dresses as a bat, and you don’t know anyone who has had their planet destroyed by the Death Star. It seems as though the artistic merit of a movie drastically decreases when we aren’t faced with “realistic” human conflict of some sort. Arguably, the only movie to win Best Picture in the history of the Oscars that you have no connection to would be 2003’s winner, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. Otherwise, you might know someone who has experienced something that has happened in all of the movies that won Best Picture dating back to 1929 or understand that the events depicted in the movies occurred at some point in human history. (RE: Ben-Hur, Lawrence of Arabia, etc.)

I stand firm in the belief that the sci-fi genre is going to grow by leaps and bounds in the next few decades. As the old blood of Hollywood ceases to make decisions on what they think constitutes a truly great movie, a new generation of producers with fat pockets and open minds will allow new directors and writers to explore the boundaries of cinema and, with that, show the general public that these movies that take place in space and have uncommon creatures in them can create an emotional response that is indicative of all great works of art. Casablanca sucks and nostalgia blinds. »

– Chuck Dulah