Visual Arts – Vo Vo

ELEVEN: I’m always curious about how artists find their medium, especially those which are less traditional. In past exhibitions, you’ve used embroidery, hand-dying, weaving, a whole range of textiles, clothing—including military uniforms—in one of your performances… Maybe starting with clothing and textiles, how did you first connect with this medium and how do you continue to develop your craft and technique?

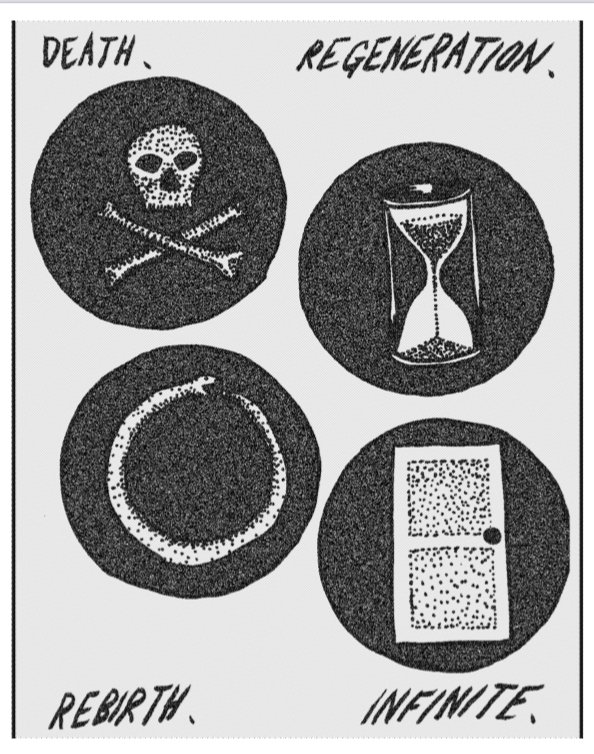

VO VO: I started off as a musician and I run a record label. I’ve been playing in [punk and metal] bands since I was a teenager. Then six years ago I got into zine making. I edited one zine for six years and I toured the states twice. Through the zine, I started illustrating. I’m mainly a performer, but since Covid I started getting into more contemporary art as an expression. I wanted to expand my illustration through embroidery and textiles. Two years ago I started weaving and embroidering but it was a slow evolution.

11: Speaking of military uniforms, you’ve talked before about this theme of American imperialism in your art, music, and performance—about connecting and reflecting on Indigenous tradition as an artist of Vietnamese descent, while also having to navigate the influence of American cultural imperialism. This really struck me, to consider folk music also a casualty of the US’s military intervention. You’ve explored this influence on folk traditions, especially in your music. So I’d like to ask you about that. When you are navigating questions of diaspora through art; how do different art mediums and performance styles shape how you explore those questions?

VV: I’m trying to use language that is typically recognized in order to deconstruct the language itself. I’ve been making folk music for the last 10 years, specifically using tropes from folk music that was brought over from 60s pop through American soldiers during the war that then influenced pop music in Vietnam. I’m then using these conventions that Vietnamese musicians took from the American influence and turning it on its head.

A lot of the music I make is similar to what you would call Americana or primitive American folk music, but because of who I am, I’m not typically recognized as American or who would be allowed into that American genre. Because I’m a Person of Color and an immigrant, I don’t fit the stereotype of Americana or folk music in this country or continent. Even trying to be a part of the genre has been almost impossible because people can’t accept someone who looks like me as part of that genre.

Similarly, I’ve been working with the language of protest—of flags, and banners, but also memes, hashtags, slogans, and graffiti—the same things we’re used to seeing as forms of protest and resistance, but then using that familiar language to pull apart what kinds of co-optation and appropriation are seen in those scenes of resistance and protest. People are so used to performative allyship, hashtagging, reposting, and liking posts without doing anything that could tangibly impact anyone in a positive way. I’m using this language to point out the hypocrisy of simply clicking on things.

I would say that I’m not Indigenous to this nation, that I’m definitely a settler-colonizer here. But I’m also a product of US imperialism. Because of US imperialism, I’ve never been able to be a long-term resident of where I’m Indigenous. There’s a lot of hypocrisy and contradiction in being a settler-colonizer. Through forced migration and war I am here, but ideally I wouldn’t be on this continent either. That’s also my focus, acknowledging diaspora as a human necessity for me and many other people due to the fact that the pattern of US imperialism continues. We saw that last month with Afghanistan and how that’s going to continue for generations, for people who are descended from those refugees and those people displaced…

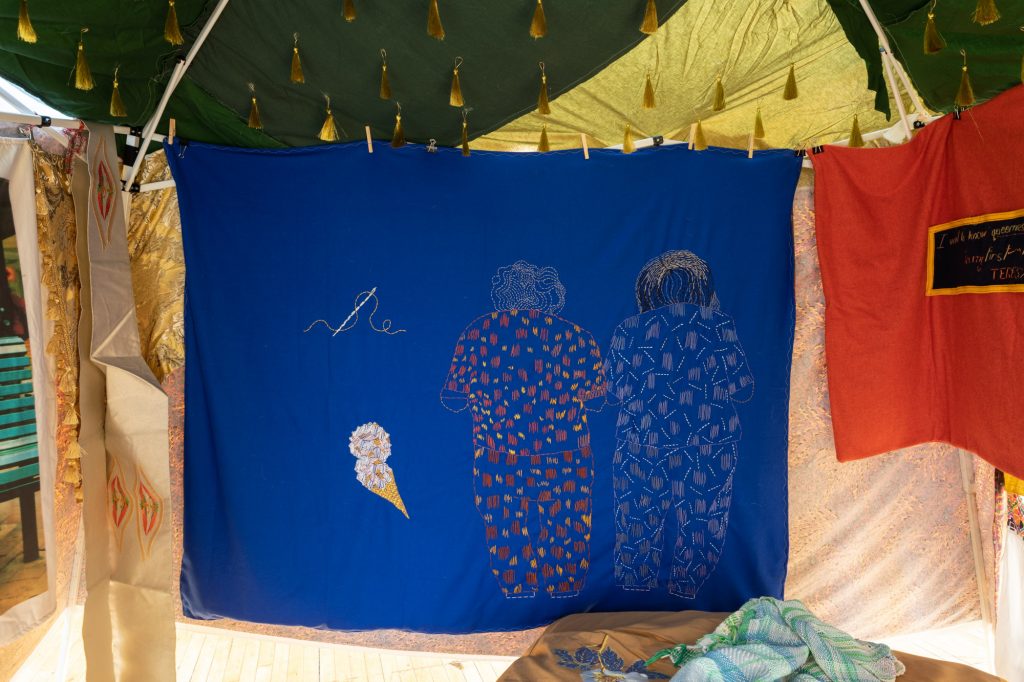

11: I want to bring up two of your textile installations: the Occupy Refuge, which you introduced as a subversion of the dominant US narrative surrounding the refugee experience, both in the Vietnam War specifically and then also more generally about the US empire at large. When constructing a counter-narrative, what was most important for you to include? What were some of the first misconceptions or simplifications that you wanted to address?

VV: Originally, I was going to do a piece responding to US-made, US-centric Vietnam war films mostly directed by white men who’d never even served or been a soldier. Initially, I was going to critique American pop culture and how, unfortunately, it’s a collection of 10-15 films which has constructed this narrative in the United States of what the Vietnam war looks like, which almost exludes any Vietnam women or Vietnamese queer people or Vietnamese femmes in any way.

But I realized that critiquing takes too much energy from the actual subject matter that I wanted to focus on, that is: queer Vietnamese people and femmes. It gave too much time and attention to these cultural artifacts made by white American men. That was my issue, that when I say Vietnam war in this country people think of American soldiers. They don’t think of Vietnamese refugees, they don’t think of Vietnamese casualties, the millions of people that were killed. They don’t think of occupation, they don’t center Vietnamese children or farmers who were killed by friendly fire. They think of this image of an American [military] uniform. That was the first thing that I wanted to deconstruct. Why even in the retelling 40… 50 years later, we’re still centering this white dude American experience. It’s pretty ridiculous. The work Occupy Refuge specifically brought to the front the ways queer and femme Vietnamese artists now are still marginalized, pushed to the side, how their experience isn’t as loud as an American veteran’s.

Again, I’m an immigrant. I’m not from here and I knew before moving it would be like this but not to this extent—that my entire family’s experience is erased so often to center the US soldier’s experience. It’s phenomenal to hear the name of your country but then not have any presence when that name is conjured up. You have no role or presence. People fill that name with US soldiers and mostly cis-men.

I’m being abstract. The piece itself was drawing out quotes and stories—the experiences of really strong Vietnamese femmes and Vietnamese queer people who are making beautiful work now.

11: As well as an artist you’re also an educator and equity consultant for organizations on a range of intersectional topics from understanding gender diversity, restorative justice, to constructive allyship and bystander intervention training. How have you found these two roles influence or inform each other? Or in other words, as you move between being both an artist and educator, how do the proximity of these roles influence your work?

VV: My last solo exhibition was more didactic. It definitely felt like I was taking on the role of the educator or consultant. But generally speaking about my work for the last 12 years—like today I spent 12 hours straight working for other people to make their space less racist or harmful to people experiencing trauma. In my work as a visual artist, I get to be a little more selfish and I get to make things I enjoy making. Art for me, along with illustration and music to a degree, that’s purely selfish. I do it because I love to do it. It’s meditation and healing for me. It’s patching past traumas for me. That’s the divergence of the two practices. That one nourishes something within me which I can’t to the same extent when I’m being a consultant.

11: Looking at your website as an artist, it looks like you have more than several upcoming performances and installations in many different locations from Cleveland, Ohio to Ontario, and in all different mediums, including a graphic novel. Is there one project, in particular, you are especially excited about?

VV: I’m doing two public talks as part of Portland textile month. The first, on October 14th, I talk more about being an anarchist and what it means to control production. After having one of my pieces censored and production stopped, I wanted to learn how to produce my own textiles. Meanwhile, I’m showing people the technology of how to overcome some of that production fear. On October 20th, Blue McCall and I, who are both queer, textile artists who make music and do performances, will be talking about queerness and the body, as an expansion of what people typically understand as a textile artist.

Vo Vo’s website