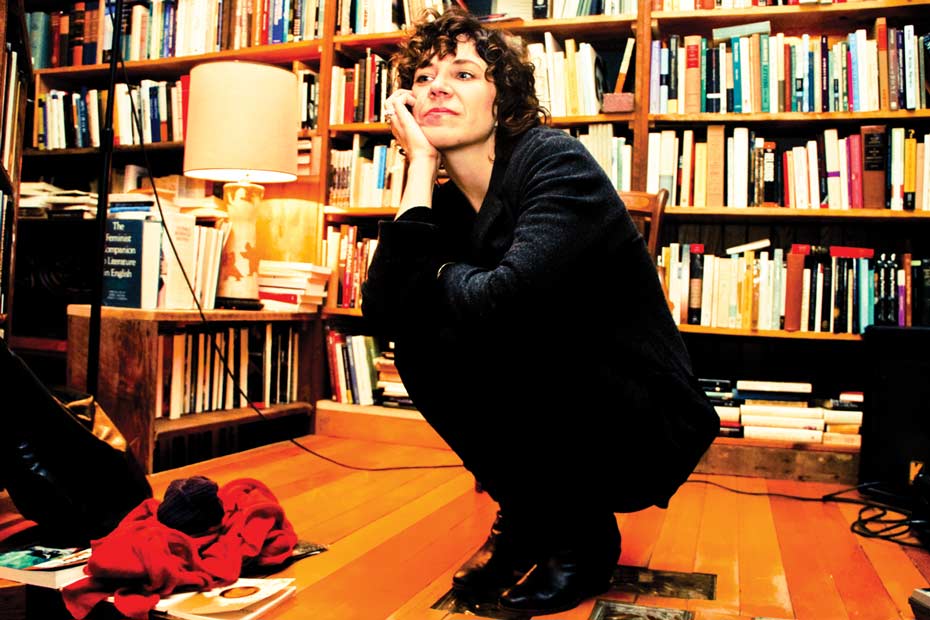

Portland Poet and Curator Liz Mehl

Imagine sitting on a blanket at Holocene or Mississippi Studios and hearing Modest Mouse cover your favorite local band’s new song for the first time. This is the concept Liz Mehl has come up with, but for poets. She based Poetry Press Week on Fashion Week, started by a single woman in 1943 to introduce the general public to fashion designers new clothing lines. This is where the runway was invented. With fellow local poet Justin Rigamonti, Liz invites publishers, press and the general public to sit down, relax and hear some brilliant poet’s work read by a “model,” performed by a dancer, or even presented by a seven year old in a ghost costume.

On the local lit scene, she believes, “It will someday have it’s own Wikipedia entry; I think it will simply be called The Portland School.” As a curator, she recognizes the level of talent we’ve been fortunate to have over the last few years, and believes that there are still many great years to come. “Do you orient yourself so as to see what’s coming, or what has just gone by?” She read, as she opened the most recent poetry reading at Mother Foucault’s Bookshop. With Poetry Press week, it’s apparent that Liz Mehl has a pretty good idea of how the tide is turning in Portland.

ELEVEN: What made you start up Poetry Press Week?

Liz Mehl: A night of drinking red wine and watching a ten-year highlight reel of Paris Fashion Week on a now defunct cable channel called “Cinemoi” was what made me start Poetry Press Week. Ha! It’s a little more complicated than that, but essentially, it occurred to me that if the fashion industry can have a biannual event designed to showcase and sell new work to a waiting public, why can’t poetry? And why can’t poetry have a runway, too?

The six-month cycle of Fashion Week (Spring/Summer and Fall/Winter) is brilliant; it brings designers out of their workrooms to gather in a single place, at a single time to show what they’ve been up to for half a year, not only to promote the work in terms of publicity, but also to sell the work. It occurred to me that if we provided the same format for poets and poetry, we could get poets out from behind their desks, let them show six month’s worth of work, and do so to an audience that includes those who have the power to publish the work, and those who have a way to publicize it as well. Inviting publishers and press, in addition to the general public, is our goal for each Press Week. We really want it to be the place publishers come (from all over) to hear and see work unveiled for publication in real-time. It allows the poets to submit to an entire room of publishers at once, potentially supplanting the downright tedious process of submitting poems individually via the mail, whether it be electronic or paper.

Another thing Justin and I wanted to get away from was that sometimes “precious” feeling at some poetry readings, where you have to be almost-deathly quiet and attentive—be the perfect audience member—and where everything is just so serious! Poetry is hard enough on the page…but to hear it, and try to listen to it, and maybe you miss a few lines, and then you’re lost. The poetry readings that took place in San Francisco in the sixties – you’ve got bars and people tuning in and out…there’s freedom to move about—it’s that’s kind of the feeling/spirit we want to invoke again at Press Week. You’re free to move around (a little—the chairs surrounding the runway might inhibit that a bit!). You’re free to take photos. You’re free to use social media throughout the programs—we encourage it!

11.So it’s the the birth of a poem?

LM: In a manner of speaking, yes. If Press Week is working how we intend it to, it will mean that when a poem “comes down the runway,” it’s the first time anyone’s hearing it. So you could say it’s being born—to the public, anyway.

Justin and I are excited that this new format for poetry is working: two manuscripts have been picked up so far because of Press Week, and lots of individual poems are being picked up by notable literary magazines. Publishers are getting it now. As I mentioned, one of the main functions of Press Week is to have poets submit in real-time. So they’re submitting directly to the publishers in the audience. We stock the audience with publishers. And we say “You’re going to be able to pick up this work tonight if you want it.” Which is why we project the poems on the wall during all of the performances so that not only can everyone follow along, but the publishers see what it looks like on the page. So they can say right there “I want to sign up for that. I’ve got to talk to this poet tonight.”

11: So you can hear it, feel it, and see it, and there’s a model?

LM: We use the word “model” very loosely, but adopted it from Fashion Week just to make the comparison strong in people’s minds. But the word “model” in this context just means anyone who is not the poet themselves. Just as fashion designers don’t model their own clothes on the runway, so we mandate that the poets don’t read their own work on our runway. And every poet is completely responsible for their own show, just like in Fashion Week every designer is responsible for their own show – picking the model, what they’re going to wear, all the rest. Ultimately we want the poets to say “Here’s what I believe is the best representation of my work.” For the first Press Week, singer/songwriter Laura Gibson, who was a good friend of one of the poets presenting, wrote original songs for all the poems, and sang them live. It was amazing. And this last time, Zachary Schomburg had Kyle Morton from Typhoon play ambient music as his reader, Michael Harper (another poet) read his poems while also using five tape recorders looping a certain line—you had to be there to believe it; it was gorgeous.

I hope PPW delivers the message that, yes, the focus of poetry is language, but there are so many great ways in which to deliver the language. What I want people to see is how poetry can come to life. The whole cross-pollination thing (among different types of artists) is nothing new. But what I hope is new is this place where new and unpublished work is delivered straight to an audience of press and publishers. And that the poetry, the poems, gets “sold” the same night!

11: You have come up with this new concept – Poet as a Producer. What is that all about?

LM: I’m all about taking analogs from other industries, and applying them to poetry, to further poetry’s cause. I was recently in a recording studio with my best friend, who’s an independent musician, and watched her work with a talented producer. She doesn’t have any more money than a poet, but she saved up several thousand dollars to afford five days with him because of what he could bring to her music. She came in with completed songs, but she asked for his input—what he could bring in terms of his own broad expertise. So I took that and said this can apply to poetry, too. I tested the concept with the poet Carl Adamshick, who in my mind seemed like he could double as a “poetry producer,” as he’s not only one of the most incredible poets writing in our time, but also has this formidable command of the pantheon of poetry. I knew he would draw from that knowledge base to oversee my project, and he did. I’d be working on some line, and he’d say, “Liz, this reminds me of this one line in this one book…” and he’d walk over and pull some totally obscure book of poetry from the thousands off his shelves, open directly to the poem, and point and say, “How does this line inform what you’re doing, or can it in some way?” His command of poetry was what I “hired” him for. He was willing to let me pay him in sandwiches and beer (they were expensive sandwiches and beer, for the record), to try this whole producer-thing out—but the goal was to see if it could be something a poet in his role could charge a very decent sum for. I told him that after this, if this concept takes off—and he’s able to charge what I believe he’s worth—I will have to save for quite some time to afford him! What I wanted to test was if this could be a way for a poet like himself to meet one-on-one with another poet, and to do so with such focus and a certain degree of intimacy one doesn’t get in the MFA program or even in a lot of editorial relationships—and be able to charge a very solid sum for this relationship. It would be crazy to think a musician wouldn’t pay their producer, and that’s exactly the sort of relationship I’m trying to incite herein. Poetry production will, and should always, involve a pecuniary exchange, just like it does in the music industry.

11: So, how did it work? Was it anything like what you’d seen your friend do in the studio?

LM: We met every day for week, just like one would in a music studio, and worked, and reworked, twenty of my poems (Carl beat them to a bloody pulp, I might add)—and came out with a chapbook-length book. It’s all still my work, of course, but Carl’s oversight and own creativity were brought to bear on it—and it’s a different book than it would have been had I not ceded a certain amount of control to him. A local publisher heard about this idea, and thought it was nicely controversial (in that no book he’s ever heard of says “Produced By…”) and thought it might make sense for him to publish such a thing. It’s set to be published in 2015. It’s called Sixes.

11: So it’s like a musical collaboration where the producer influences the sound? That reminds me of Dave Grohl’s new project.

LM: Yes! And if you know Carl’s work, you can just begin to hear it in the poems—just like a music producer’s sound can usually be picked up in the work he/she produces. Another aspect I think is great here, is if it’s on the shelves and my name isn’t recognized, they might pick it because they love Carl’s work. In the music industry, many new bands and/or artists are getting discovered because of who they’re being produced by—and again, why shouldn’t poetry have its similar arrangement?

11: You might end up launching careers. Kind of like an opening act for popular band?

LM: Exactly, that’s part of what it is. If the concept of production in poetry is controversial in any way—I’m grateful. Anything, any thing, that can get people to pause for a second and ask, “What the???” when it comes to poetry, in my mind, is good for poetry. I will continue to hunt down ways we can turn the popular tide back toward poetry, which I agree is “a major art form with a minor audience.” That needs to, and will, I believe, change as we all do what we can to ensure poetry stays relevant—and present—in the minds of this, and future, generations.

11: So, what’s next for Poetry Press Week?

LM: Justin and I plan to take Press Week to Chicago, New York, lots of big (and even small) cities in the next two years or so, if we can find funding; and in five years, we’re really hoping to take it internationally. There’s no continent we’re not aiming for. Watch out Russia, we’re coming for you!

-Scott McHale