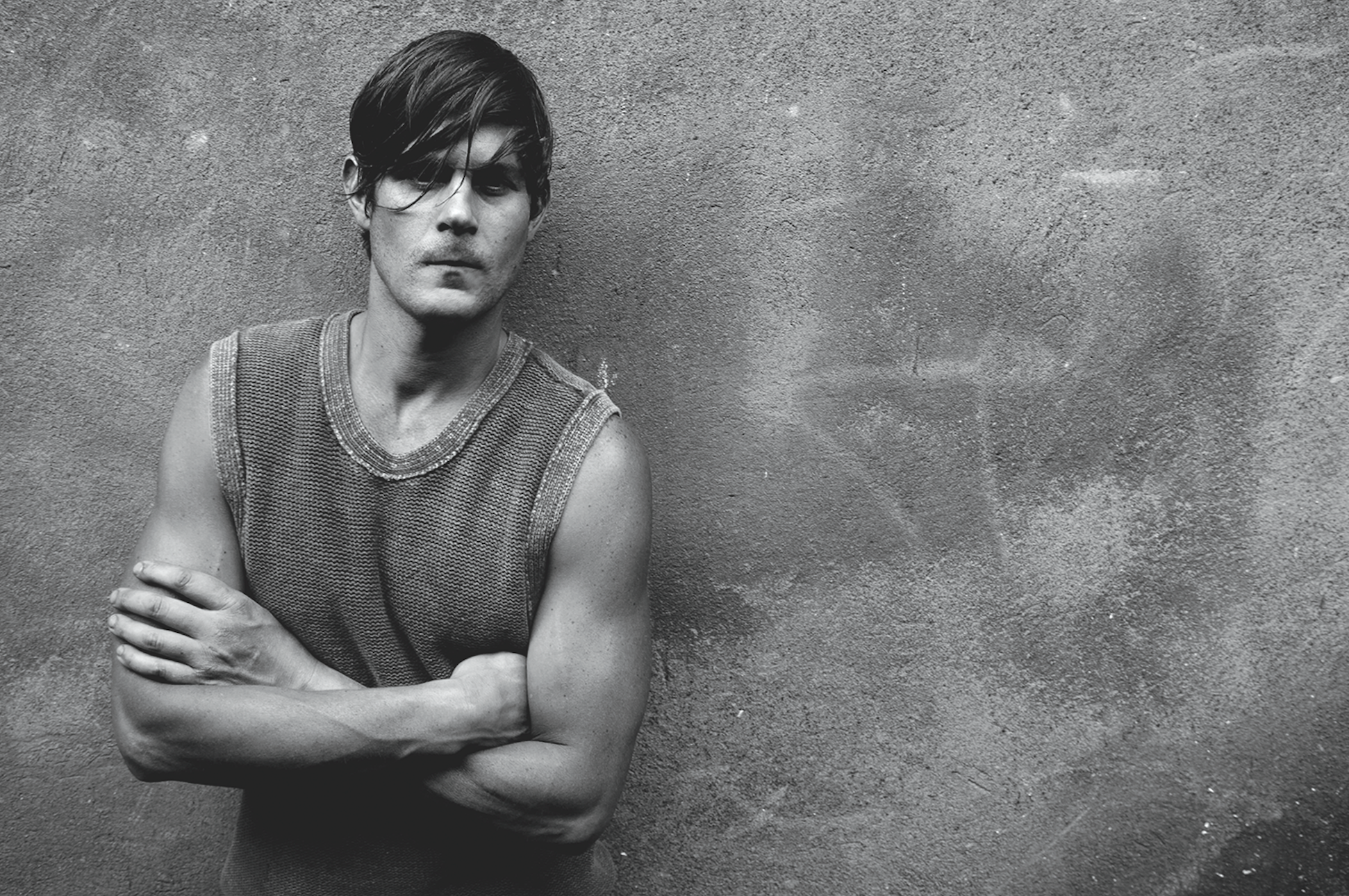

Portland photographer Joshua Zirschky

In this fast-paced society, full of distractions and bombarded with advertising, it is easy never to step outside your self-focused experience. Conflict photographer Joshua Zirschky has travelled the world to witness and peer through challenging perspectives. Many of us find it too difficult to acknowledge that human conditions can still be so brutal in the modern world, but Zirschky seeks to expose that a large percentage of the world lives in a very different way than much of the United States.

Eleven: What got you into conflict photography?

Joshua Zirschky: It started when I was really young. I was probably in sixth grade when a camera first came into my hands. Even at that young of an age, I was studying the Holocaust and had become intrigued by the power of all the images. My parents moved me from a private to a public school in sixth grade that had a photo program that I was able to participate in from junior high on through high school. I think where it really clicked was when I was studying in Montana in college, where my professor introduced me to Magnum photographs and this completely shifted my perspective. I spent a lot of time studying and researching photojournalists who had really inspired me to do the type of work that I do now. Initially, they allowed me to see that there is something really big going on. It has been an incredibly humble experience attempting to discover how I can do the work and follow in the footsteps of these individuals who inspired me. It’s this work that has driven me.

11: What do you mean about being inspired by their work? Are you talking about the quality of the photography or the message?

JZ: The message mostly, and also the voice. I am attempting to discover how I can get into these areas and how to use the camera as a tool. Photography allows me to give a voice to some of the people I feel are the most voiceless, and I have been attempting to be able to share their stories through imagery. Some of these individuals have endured incredible situations and experiences and suffering. So my challenge has been about how I can show that perspective.

11: Why is it important for people to be exposed to this perspective? Why do you think we should we care about people who are “voiceless”?

JZ: I believe that it is a commandment, like looking out for the orphans and the widows, a calling. Since I was in my twenties, I have travelled to really intense areas of the world — South Africa, Botswana, Zambia, Somalia, Egypt. Every one of these places are incredibly challenging for people to live in. I feel like this is important because there are thousands of human beings out there that have absolutely nothing and live under extreme totalitarian regimes that are keeping them enslaved in bondage and poverty, and they are not going to get out of it unless people know about it. Maybe my photographs are not going to have any kind of impact, but I think it would be worth it if even once someone sees a photograph that will ignite some awareness.

11: How did you find the opportunities to get involved with this type of work?

JZ: All of it has been non-profit work for the most part, all through word-of-mouth both while living here in Portland and while I was traveling. The only reason that I ended up traveling to the Middle East was that one afternoon, as I was returning some snow shoes in Colorado, I ended up meeting a really wealthy oil man who had seen my photographs. He was connected with a whole group of Lebanese men who work in extremely impoverished areas and who hired me on to work with them. This was the bottle neck experience that opened up so many other experiences and doors to me. Some of the organizations I worked with include Habitat for Humanity, Amnesty International, World Vision, Red Cross, United Nations, Doctors Without Borders, and the Near East Foundation (based out of Jordan).

11: Is there any impactful experience that really stuck out to you during those travels that you would like to share?

JZ: I could sit here for hours and tell you hundreds of stories regarding small moments that really capture the experience. I recently went to Guatemala and ended up getting led by seven nurses who took me up to see this 105-year-old woman who was living in this one-room cabin with only one light bulb. I spent six or seven hours with her just photographing her and sitting with her and talking and getting to know her. She had been widowed for 40 years, and she was a Christian and she was crying her eyes out because in the time she had spent on this Earth she had experienced so much joy. She kept saying, “I can’t wait til I get to meet the Messiah.” I was in tears. I couldn’t believe it. It brought hair up on my neck. It was such a contrast to the many unhappy people I see here every day.

On another occasion, I got invited to the Addis Ababa Fistula Hospital (also known as “Hamlin Fistula Hospital”), which is a women’s hospital in Ethiopia that Oprah actually did a segment on. This is something you really don’t hear about in the first world countries, but apparently when a woman has a miscarriage it can rip the bladder and these women are left incontinent. Doctors are now able to sew and repair this issue at this hospital. This condition has historically been a cause for shame and marginalization for many of these women with these obstetric fistulas.

11: You participated in making a book in Guatemala called Libre Soy. Can you tell us about that project?

JZ: That was a project that I did with a guy named Richard Myers and a woman called Allison Voigts and she was a writer and he more of the organizer. He was very connected to many of the missions and clinics that were down there. He saw another book I worked on, Brother/Sister: Stories of Transformation from Vietnam and Cambodia, that I made with some other writers in Southeast Asia and he wanted to kind of emulate that project. This was a similar kind of content to these clinics that were set in these incredibly impoverished areas. Inspired by the demolition left over from the Reagan era, this area was the setting of guerrilla warfare and mass murder. This book focused on the role that these clinics and missions had during this time period and what is happening in these areas today.

11: Have you ever been scared going into any of these war torn areas?

JZ: Oh yeah.

11: What was the scariest thing that you recall happening?

JZ: Probably the scariest thing happened in Ethiopia, where I was on the back of a motorbike and got pulled over by a whole truck of military guys. They all jumped out to confront me. One guy flipped open a knife and grabbed the camera around my neck and cut all the straps to get the cameras I had. He took my backpack, my gear, everything I had, including my passport. They then took me to their compound to interrogate me about what I was doing in this specific area. I ended up getting the cameras back from them but they popped the backs of my cameras open and stripped all the film from them, which was a huge bummer because of all the work that I had on that film. I had spent all day photographing the surrounding area. I had all these beautiful shots of these women praying in front of a church, among tons of candles, and all these gorgeous colors all around them.

11: Why is it important to understand the historical context of a place for your photography?

JZ: When you just thrust yourself into these places you have to know what is going on in order to know the context of the people’s experience. When I go into these areas I study a lot too. History fascinates me and it really helps me to develop into a better photographer. The knowledge of history helps you to realize what is happening and how to best capture the truth.

11: How do you feel your work compares to other photographers in the US?

JZ: I feel like Portland is a hyper-sexualized place compared to the many other places I have traveled to and a lot of the art scene is all about sex. I’ve noticed a lot of photographers who seem so focused on just shooting the next sexy tattooed woman. I don’t mean to diminish modeling photographers. I just don’t think it is interesting or impactful to take pictures of just pretty women. I want to represent something that is happening on a global scale. I don’t want to put down fashion photography. I studied that too. It’s very unique and artistic and I find it intriguing in the sense of the artfulness of it. I want to get more involved in that field too, but I just don’t want to lose the focus of my work.»

– Lucia Ondruskova