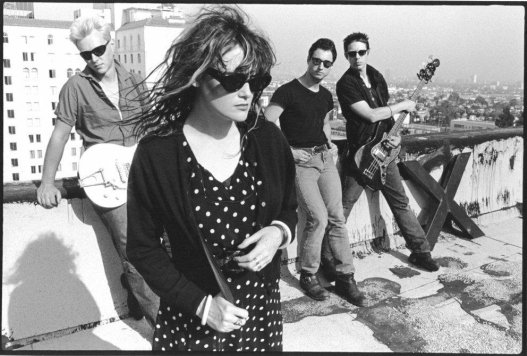

Interview With Exene Cervenka of Legendary Punk Band X

Live in Portland December 28 | Crystal Ballroom

Punk is still punk, no matter where it is. Even forty years later. Even in the Grammy museum. This is the conclusion one reaches after spending long enough with it–a zen-like rejection of the rejectionist philosophy that came to define the countercultural brand of rock forged in the societal crucible of the 1980s. This is the conclusion reached by Exene Cervenka, frontwoman/singer of X, the band whose work would come to be emblematic of the then-burgeoning, now legendary L.A. punk scene.

Forty years is at least a few musical epochs, enough time for the dominant aesthetic to come and go, vacillating as it will between opulence and austerity, and to survive that long holding onto anything is a small miracle. Perhaps a part of the key is not holding on, practicing the kind of non-attachment that seems central to the punk philosophy. Surviving by drifting, changing as the times change, only to end up decades later back again where you started, finding that the voice you found all those years ago is the one with which you still speak, with which you were maybe speaking all along.

ELEVEN spoke with Exene Cervenka over the phone about punk rock, museums and awards, and how to navigate a forty-year career.

ELEVEN: How are you? Where are you?

Exene Cervenka: I’m good. I’m at home, in Southern California.

11: Is that where you’re spending most of your time these days?

EC: Yeah. When I’m home I’m here. I’m not home a lot, but when I’m home I’m here.

11: You guys have had a busy year.

EC: Yeah, we’ve had a really busy year, we’ve toured a lot more than usual. I mean, we tour every year, but we’ve toured a lot this year. We did the Dodgers thing, where I threw out the first pitch, and John did the national anthem at a Dodgers game, that was amazing. We had the Grammy museum opening, we got this thing where the city council of Los Angeles gave us a proclamation saying we’re great, all kinds of stuff like that this year, and we’re going to keep it going next year. It’s very important for us to keep going, so we’ll see what happens next year.

11: The number 40, what does that number mean to you?

EC: Well, it means we’ve been around a long time, and that we’re lucky because we’re still here. You can’t make stuff happen. There are things you can make happen if you work really, really hard. You can have a long career, or a good career, but you can’t make yourself stay alive. So we’ve done a pretty good job of keeping going, and I’m proud of us, I’m happy that we’re still playing.

11: And you’re about to start your West Coast tour?

EC: Yeah, we’re doing our usual tour. We usually play Portland, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Orange County, San Diego, and then we throw in some other cities, but that’s what we’ve got this year. It’s not as many shows as we usually do because we’re playing bigger places. Holidays are crazy for us, we don’t usually get holidays at home, but you know, it’s ok.

11: You’ll be in Portland on December 28 this year. Do you remember the first time you guys played this city?

EC: You know, I don’t remember the first time we played in Portland because it was 40, 38 years ago. I do remember one time John and I were exploring around the city, we were down in this area that was all warehouses, we found this little biker bar. It’s probably a hipster bar now (laughs). We were pretty adventurous. We’d always explore new cities, just walk and walk and walk. But it’s changed a lot over the years.

11: Yeah, I imagine you’ve seen a lot of developments in these cities over your career. You think that’s for the better or worse?

EC: You know, there’s a difference between revitalization and gentrification. I think most of us are not big fans of gentrification, it pushes people out and ruins things. I sometimes think of when I go to bars that I used to go to, and everything’s on the floor and they’re playing this weird music, and I’m like, “Where did the old people go?” But you know, sometimes without certain changes, those cities would be gone, they’d be ghost towns if people didn’t put money into them.

11: You guys have been known to be political with a lot of your records, and you’ve been known to speak on issues you feel passionately about. Do you still think that you have an obligation as an artist, to be that conscience?

EC: I do for myself, but I mean the way things are now in this country, I’d be afraid to say anything pro or con on just about anything. There are a lot of people that are having problems, but that’s as far as I’ll go, you know? People are so strident, there’s so much anger that it’s really a volatile time to voice any opinion. Free speech is kinda a thing of the past in this country. I think everybody hopefully has the same goals, which is we want a better society, we want people to do better.

11: For this tour, you have a lot of material to choose from, how do you go about picking a set list, do you stick with something or do you like to mix it up?

EC: We do have a lot of material, and we do mix it up, but it’s mostly the first four records, that’s the stuff that’s good, that people want to hear. We do play songs we didn’t used to play live, like “I Must not Think Bad Thoughts” and “Come Back to Me,” those are songs that have vibes and saxophone, so we have another person playing with us. We play the first four records, and every million years we throw in something else, if we have time to rehearse it and it sounds good.

11: Do you find that those songs have changed for you over time, and maybe revealed themselves in ways that you didn’t think about when you were writing them?

EC: I had to write some lyrics out for our Kickstarter thing, we did this Kickstarter and people got prizes for giving money, one of them was handwritten lyrics, which maybe sounds easy at first, but if you mess up a word halfway through you have to start over. It’s taking me a long time, but I like doing it. But I was writing the lyrics, and I sing them all the time, but it’s different when you’re writing them. All this stuff, as I was reading it, I was like, “Is that really what I said there?” It was a kind of a weird moment for me. You know, you sing a song but it’s different from reading it, there’s meanings that maybe you forgot. It’s weird, you know?

11: Speaking of your writing, I was looking at your collaboration with Lydia Lunch, and I came across the lines “I’m painting the town blue / I’m in a perpetual state of despair.” Does that line still ring true?

EC: Eh, that was probably because my heart was broken by some guy or something. You know, I’m a writer more than anything, so I’ll just put words together. But no, we’re not discouraged by that recognition. When all of us bands started out with this punk rock thing, the goal was never to sell records or get in the Grammy museum or the whole thing, but when we started doing well and some other bands started doing well, it was nice, you know, it’s nice to make a living playing music, and I’m happy for people who can do that, especially if they don’t have to compromise to do it, and people like it. I mean, that’s the best thing in the world.

11: Do you think that putting what started as this countercultural art in a museum, do you think that changes it, to have it be recognized by these big important bodies?

EC: No, because we’re the kind of music that should be recognized. You know, bands like The Weirdos and The Screamers and The Plugs and The Big Boys, all these bands from the ‘70s, they should definitely be recognized, and talked about.

But you know, when it comes to Grammys, that’s not for regular people. It’s like politics, people think they’re involved somehow in this hierarchy of power, and they’re not. When people are in power, they are often not in power because they’re really talented or because they want to make the world a better place, but because they want to wield power, and sometimes when you see all this stuff, you think, “No wonder certain people get famous, and no wonder people who are good get overlooked.” A really great band has nothing to offer a guy with a private jet who wants to sleep with underage girls. That guy doesn’t care. He’s not going to make somebody famous because he thinks the music is good, or because he really believes in their project, that’s not why he’s up in that position of power–to be altruistic and help expand the consciousness (laughs). I think we always knew that, but now the public knows it a little bit better.

11: Going back to that line I quoted, which has that repetition of “disrepair, dissolving, despair, discouraged,” or songs like “Johnny Hit and Run Paulene,” or “The Once Over Twice,” this way you have of taking a word or phrase and changing it, putting it on its head, or changing and meditating on it–is that a way of writing that always came to you, or something that you focused on?

EC: Yeah, it comes naturally to me, it’s my style for sure, and you know, I really love country music, it’s probably my favorite kind of music, and it just so happens that I have an affinity for that kind of writing because country music is as well, it’s always playing with words. You know, “If I could have my wife to love over” instead of “My life to live over,” stuff like that. And I do work really hard on my writing.

11: Do you find that that’s your main creative output these days, aside from playing with X?

EC: Actually, I have an art show up right now here for two months, and I only had to make one new piece for that because I have so much, but yeah, I go back and forth between everything, you know? I work sometimes a regular job too just so I don’t run out of X money. It’s expensive to live where I live. I juggle like everyone else in the world, but I’m happy. I like working hard, I think it’s an important thing to do.

11: Your art show that’s going on right now, what medium are you working in? Can you describe what it’s like?

EC: It’s collage, I’m a collage artist. I’ve been exhibiting it for about fourteen years. You can see it online, but I have collections of things I’ve found on the street, or people have given me over the years. A lot of it has an Americana influence, of course, because I live here. It’s just old stuff put together in weird ways. Sometimes it’s humorous. It’s never very overtly political unless you read into it. That’s what I love about art, it’s up for interpretation. My first big show was called America the Beautiful, and all these people thought it was going to be pictures of Ronald Reagan with a knife in his head or something (laughs), and it was like, “No, I live in a really beautiful country and here are all these things I found over the years that I thought were neat.” I stuck em all together and made stories out of them, it was funny.

11: Speaking of artists, who are some people that you think are doing important work right now?

EC: Well my favorite band right now is Skating Polly, they live in Tacoma but they’re from Oklahoma City, and they’re just finishing up a record. They’re super young, a sister and a brother, and I’ve known them a long time. They’ve made like five records now, they’re really amazing, most creative hardest working band I’ve ever known, and they’ve been that way since they were children. I also like Folk Uke a lot out of Austin, it’s Amy Nelson and Cathy Guthrie, they’re folky, really beautiful voices, and funny, really funny songs. There’s a lot of bands here locally I like that don’t get to tour, because life is hard. Amy’s brother’s band I like too a lot, Insects vs Robots. I like Petunia and the Vipers, they come down to Portland a lot, I think.

11: So clearly you’re still pretty involved in the scene?

EC: Yeah, I see a lot of bands. I get a lot of music, and I think right now is a really good time for music. It’s kinda like when we started, except there’s ten thousand more bands. I mean, there’s no way you’re going to make it big in music unless you’re Selena Gomez or something, so why not just make the best music, have the coolest merchandise, have the most fun at shows, work with your friends, work hard, be proud of yourself for having a wonderful fun life, and work a regular job if you have to too. So many bands are doing that now, they’re not trying to get famous and rich, they’re trying to make great music, and there’s so much of it out there.

11: Probably the thing that’s the most different from when you were first coming out and now is the internet, which despite all the things you could say are problematic about it, it’s this DIY platform that enables bands to exist on a smaller scale.

EC: Yeah, and I know a lot of kids who’ve gotten their musical history through Youtube videos, people who died seventy years ago. And you can look up, say, some old jazz or blues singer now, and she’ll have 80,000 views. She didn’t sell 80,000 records when she was alive, and probably in the sixty years since she died she didn’t sell any records, but now 80,000 people are listening to her music, and I love that. Musicians and filmmakers, artists, they live on in their work, and they know that. They know they’re going to die, but they’re going to die in a way that’s beautiful because they’ll live on, their music will be discovered for generations and generations, and they’ll bring people happiness and inspire people, and that’s the best thing you can get out of this world. I’m not saying you have to be famous, but you have to leave behind something for people to remember you by, to leave the world better.