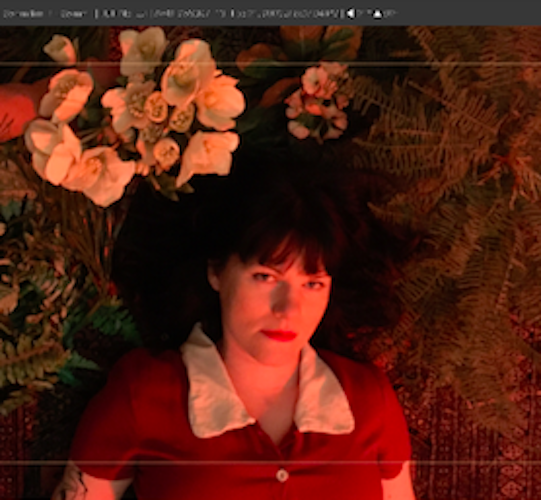

Local Feature: Deathlist

Jenny Logan couldn’t have timed the release of her band Deathlist’s latest album, You Won’t Be Here for Long, any better. Steeped in gloom, doom and droning darkness, Deathlist’s fourth outing conveys a bleakness apropos of our current weird and warped times. It’s an uncompromisingly introspective and revealing soundtrack teeming with heartache, pain and transcendent beauty.

Challenging herself to work outside of her comfort zone (which is saying a lot for a musician also clocking in with local bands Bitch’n, Pungent and Dress Forms), Logan arranged this Deathlist record around improvised and recontextualized synth tracks. The results are a mesmerizing and haunting mix of goth, synth-wave and post punk that find an artist coming to terms with old ghosts and discovering universal bliss while it’s there for the taking.

Eleven: As a performing artist, how are you coping with the current COVID-19 pandemic?

Jenny Logan: I was thinking today that it’s nice to have a record coming out because I have something to focus on. I still have some work and stuff that I can do, but for the most part, not a lot is going on in my life. I’m fine, but it’s good to have something to look forward to.

I’ve done a live show from my basement through this woman I know in town [Anne Curtis from Captive Audience] that’s doing a house show series on Facebook. And that was actually pretty fun. I miss performing a ton and I was kind of ambivalent about doing this [online] show because I’m like, “Whatever. There’s no audience and stuff.” I’ve never gone on Facebook Live either, so I didn’t know what it was like. But when I went live, I was like, “Oh, I am having a shared experience with other people, even though they’re not ‘here’ here.” You know? And I did feel like I had some of that community back.

11: So, you could get crowd reactions as you played?

JL: I couldn’t see it in real time while I was playing ‘cause my camera’s on and stuff. But I could read [the comments] afterwards and it was fun. So, it’s kind of like a show, I guess (laughing).

11: What are you doing to stay busy during shelter in place?

JL: I was already kind of a loner, anyway. I’m reading a lot, playing music; I’m thinking about going back to school, so I’ve started studying for the G.R.E. for grad school. It keeps me busy.

It’s nice to feel like I’m working towards something, because I was working on music every day. But now I just have this feeling: when am I ever going to play a show again? Like, this year? Even if bars start to open up again, is anyone even going to want to go to a fuckin’ show?

I felt like I needed to be able to work on something other than music, too. Even though music is a very big outlet for me, it’s hard to think of a future with that as my occupation. The majority of money I’ve made off music is from playing shows and touring.

11: So, that vital component of making a living as a musician has been completely decimated due to the pandemic?

JL: People are trying. Like, Bandcamp is doing stuff where they’ll waive their revenue share on certain days so you can get more money from online sales. People are still buying my records online, which is cool. I get some money from my streams on Spotify and YouTube and stuff like that. But you can’t really plan for it in the way you can plan for a guarantee from a show.

11: How did your new album, You Won’t Be Here for Long, come about?

JL: I have been recording with Victor [Nash, producer at Destination: Universe] probably for about four years now. I kept telling him I was going to make a synth record, but I never did. So, one day he’s like, “I’m coming over. I have a synth and a little amp and a stand, and you can fuck around with it and stuff.” And that kinda forced me to get in that head space.

Then, I booked a session with him where I improvised synth notes, or riffs or whatever you call them (laughs). I played it to a click and then I played a drum machine over it. I improvised maybe five of those. I took them home and wrote melodies to them. I came back to the studio and tweaked the stems a bit and then recorded vocals.

11: What did you record this on?

JL: It was recorded electronically. It’s at [Victor’s] studio, and I want to say it’s… Pro Tools? I’m not, like, a recording guy (laughs). He would just send me home with MP3s and I would loop them and kind of sing along to them or play them on my guitar.

11: Was it difficult to arrange the songs around the improvisations you guys created?

JL: It’s less hard than you might think. I wasn’t, like, playing jazz (laughs). I’d play one part over and over and then maybe a second part. Then, because it’s digital, we could cut it up and make different sections. Like, “Okay, this part’s going to be the verse, this part’s going to be the chorus, and we’ll make this one repeat this many times.”

If I was just, like, stream of consciousness jazzy improvising, then yeah, I think it would be hard. But I went in there with the intent to make a riff, and then make a song out of it.

11: When did you guys start recording this album?

JL: I wanna say November or December.

11: Did you play all of the instruments on this record yourself, or were there other musicians involved?

JL: I did everything, except there’s two tracks with live drums. I didn’t play those. That was my [live Deathlist] bandmate, Elly Swope.

11: Is it difficult to write and record these songs that reveal a lot about yourself? Is it hard to put yourself out there or do you find that it’s easier to do through performing?

JL: For me, it’s way easier in recording. You don’t answer to anyone in that moment. No one’s there to be, like, “What…?”

There was a lot of fear about revealing the abuse I experienced as a child. There’s a lot of secrecy in my family. Even now, as an adult, I’m afraid to go on record—even, like, in a song—singing about something that happened to me. It’s ingrained in me—or, like in my reptile brain—to be like, “Don’t tell anyone about this.”

But what I’ve found, even talking about it in interviews: nothing happens. Nothing bad happens, I should say. Some people have responded to it positively, and that, for me, is worth that fear or whatever anxiety that’s caused me to be more open about stuff.

I think it’s worth it for me to put a bunch of personal shit in my music. That’s really the only thing I have to offer as a musician. Everybody plays fuckin’ guitar, you know? My songs aren’t really breaking ground. I think the thing about them that makes them valuable at all is just that I am a person trying to communicate with other people.

11: Where your previous Deathlist records were mostly about your dad, this record seems like it’s about other facets of heartbreak.

JL: This one is definitely less about my family and more about relationships. There’s one song on this record [“Night Face Regetter”] where I just describe ending a relationship I was in. It wasn’t abusive, but it was just really shitty, for circumstantial reasons. I went to the ocean by myself and I cried for two days. It was super dark (laughs). But also, really beautiful, too.

That relationship ended, but it took a while to end. When I think about it, it’s painful. But when I listen to the song, I’m like, “This is my statement. This is what I made out of that.” I love this song and I think it’s beautiful. It makes me feel like I have gotten over that experience in some way.

11: Did you draw from any influences while making this record?

JL: I had this office job for the better part of last year, and it became this ritual that when I got into my office, I’d put on Suicide. I thought a lot about what do I love about Suicide, that I can listen to it every fuckin’ day. I think some of that is their music is really repetitive, but it’s fleshed-out enough that it just doesn’t really get old for me. And I think that is what I was trying to go for, using those kind of synth landscapes.

My last record—A Canyon—I kind of go off in this weird baroque guitar jam throughout. But with this one, I was just like, “I’m not going to do that. I’m going to get down to the essence and have it be this bleak, repetitive jam.”

When I go and I’m making a record—especially now that I’ve made a few—now I’m thinking more like, “What am I really trying to say and is it different than what I’ve already said? And if it’s not, then why am I doing this?”

11: You’re releasing this record independently on Bandcamp. Are there any plans to release a vinyl, CD or cassette version?

JL: There’s a cassette in the works. It’s super limited run because I don’t know when I’ll be able to play a show. I finished this record in March and I’m very proud of it, and up until now I’ve mostly just self-released my own stuff. I was thinking about shopping this one to a label and see if I can get a booking agent and really go out and sell it, then all this [COVID-19] shit happened. It was either wait until fall or I could just self-release it in the shorter term. So I ended up deciding to do that, and I’m glad I did now, because I don’t think anyone is touring in the fall either.

11: Given the fact that we’re living in some pretty dark times and it feels like we’re all screwed, what better time for the release of this record, huh?

JL: You know, the single, “You Won’t Be Here For Long,” came out right when shit started to get real with the pandemic. I felt like, “Cool. It’s prescient.” But also, like, “Fuck.” My intent wasn’t going to be, “We’re going to die!” Even without this, though, you don’t really have a lot of time on Earth, you know?

11: How long have you been playing music here in Portland?

JL: The first time I played in Portland was probably in 2004. I toured up here from Sacramento [while in the band Oh Dark 30] and I had never been here before. We played in this place called Hotel; it was an abandoned hotel that had been squatted into a venue. It was fuckin’ rad. I remember going outside after we played and I saw the three members of the band The Planet The ride by on their bikes, and I was like, “Portland is fuckin’ awesome!”

When I moved here after living in New York City for five years, I had it in my head that I wasn’t going to play in bands anymore. I came here for law school, so I was like, “I’m going to move to Portland and put this teenage shit behind me and be, like, a lawyer.” I graduated and moved away, and then I moved back to town in 2014. And that’s when I joined Summer Cannibals.

11: How did Deathlist first come about?

JL: During 2015 and 2016, I was on the road with Summer Cannibals and I was starting to feel burnt out playing bass in a band where I wasn’t involved in writing the lyrics. I had something to say that I’m not getting out there, but I’m performing every day. Which is kind of a mindfuck too, because you feel like you’re performing something that is not you. So, for me, Deathlist was the thing I would do between tours to have my own voice.

11: What are you hoping that the listener takes away from You Won’t Be Here for Long?

JL: Everybody’s dealt with heartbreak. I think just the idea that you can also make something out of it that’s not just pain; you can also make something that’s interesting and beautiful out of it.