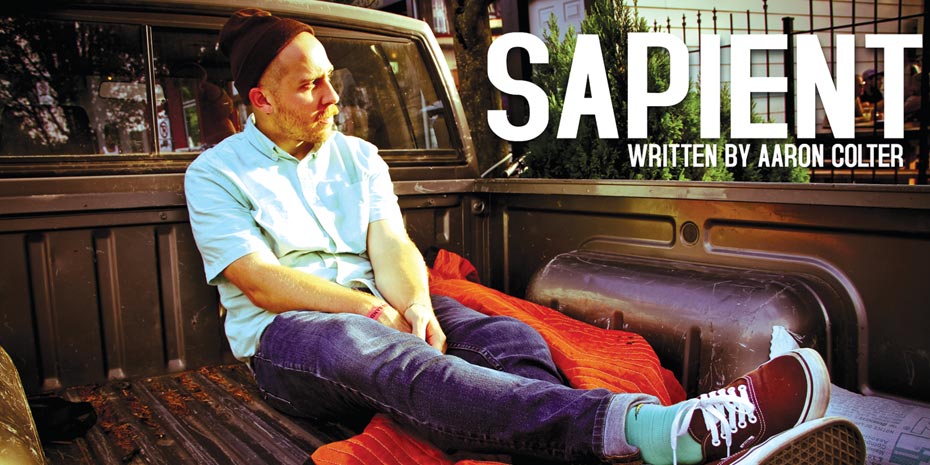

Sapient

With a proper Portland mustache and wearing flannel, at first sight Sapient could be a banjo player in a local indie-folk group instead of the experienced hip-hop veteran that he is. Even if he weren’t a talented creator in nearly every aspect of his craft, Sapient would be an authentic testament to the cultural permeation of rap. Operating out of Portland for years alongside other gifted MCs under the Sandpeople moniker, he has built a following through consistent releases, tours, and collaborations. His most recent album, Eaters Vol. 2: Light Tiger, has been garnishing praise since its June debut, and is the catalyst for a western tour with Illmaculate, which kicked off at Mississippi Studios. ELEVEN had the chance to speak with Sapient before he left about what it takes to be a successful DIY musician.

ELEVEN: When did you start making music?

SAPIENT: I was always around a lot of music. Both my parents are musical. My mom’s more classically trained and does violin and piano, and my Dad’s just kind of like—you know—plays guitar and is more self-taught and is into rock. I’ve always been around guitars and and piano, but never had lessons or anything. I didn’t know if it was something I was inclined to or not. It was sorta just always around, you know? After I started getting guitar, I started to get into more stuff. I’d smoke weed and play guitar *laughs* but never take it too seriously.

But then, when I really fell in love with hip-hop and starting doing it that way. . . I don’t recall the first thought that happened—I don’t have that on memory. I just started making hip-hop with my own tape deck. I had a tape deck and stuff, a little 8-track. I remember getting into hip-hop around end of middle school or the start of high school, and I kind of started free-styling with friends like everyone does. And I’d download these beats off of Napster that I liked, and I would kinda like write these raps. I don’t remember exactly, but maybe like sophomore year or something like that. I would have my CD players pointed with the burned instrumentals of the beat, and my tape deck had a microphone. And so I’d let the instrumental play and hit record and try to find the right distance and volume to mix. I made a bunch of tapes like that and didn’t know anything about song structure. I was just rapping and doing my thing.

I really started to get tech when I would go through and use the CD player’s tape deck to play the backup vocals that had been recorded through the first time—record that, then play it back together with the main vocal again. The sound would get significantly worse, and that’s when I started to doing some research to get a little 8-track with a guitar, drum machine and stuff. I made like six albums in high school that I don’t want to see the light of day. I just became a fiend for it.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/149731592″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=true&show_comments=false&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]11: Have you been able to make art your only job?

S: I sell beats, and do mixing and mastering, cover art, and illustration commissions. It’s just because they’re usually fans of my music. It’s all still part of my craft. It’s not like I dig ditches or anything. I’m trying to narrow the spectrum. It starts to take over and that hurts the music. I kinda got into that. My kids are little and it’s hard to leave when you’re trying to develop that close bond. It’s very important to be home. My oldest just turned five and my youngest just turned one. So, you know, I haven’t really toured much. I’ve eased off a bit.

11: What’s your end goal with balancing work and family?

S: I’m not trying to write a hit in the sense of commercial radio or whatever. As far as success, I don’t really have numbers or the end result. It’s a tricky, psychological thing. There’s the motivational aspect: that if you stick to this, you should be to ‘here.’ But at the same time, I have to stay focused with being happy with the success I do have. Even though it’s crazy at times, and the scramble, with money coming in from different directions, and my financial responsibilities are heavy. . . sometimes it doesn’t feel like gaining, you know what I mean? Especially when I see peers living out on the road and doing what you have to do.

For me, making the choice to be at home with my family, I know staying at home is the most important. I don’t want to get into a weird vortex and then it affects the music. I don’t want to go down the path of thinking about writing songs that would be a success—that’s not why I got into music, and that’s not what people like about me. But basically, the end goal would be to tour once or twice a year and still be able to paint for fun and still be able to take care of my family. I think it’s right around the corner. I just want to be able to relax a little more, you know?

11: How did your song about Macklemore come about?

S: We’re, like, music scene friends. We’ve done some songs together and stuff. It’s all just tongue and cheek. Some people say it’s hating, but not at all. I like to see him be successful, much more than most of these people that are famous. Macklemore can spit. You could see him be a little less communicative, though. I texted him during the Grammy’s, and before I’d always hit him up about new videos and stuff and he’d hit me back. That’s why there’s that line “I texted Macklemore / he don’t text me back no more.” And everyone’s like, “fuck that blah blah blah,” but it’s not like that.

We were music homies, but there are a lot of people that are much closer to him. Obviously it’d be cool to go on tour with him, which is why I joke about that. But, it’s not like. . . I mean, as soon as he blew up I’m sure all the parasites came in. So I don’t hold it against him at all. It’s all very precise what they did—he filled that hole in the industry that needed him and that’s pretty amazing. But, you know, it’s hard when the babies are screaming and I’m stressing about money to see him on tour and think—”I used to play in bars with that dude.” Yeah.

11: Where do you think the industry and scene are going in the Pacific Northwest?

S: I feel optimistic about it, for sure. The industry and doing it yourself kinda overlap. It’s so broken apart in so many ways. You can hire people just like a label can. If you just have a credit card or some money—a label just hires a publicist and puts money into things. So, I do feel optimistic about the industry, and not just hip-hop. It’s not just suits deciding what’s good. Obviously there’s still Pitbull featuring Ke$ha and stuff. I don’t think the industry’s ever going to make a huge turn to where suddenly what I’m doing is the thing.

People who like music like Pitbull and Ke$ha, it’s not like they just like different music, they like it for a different reason. They want to move to it. They don’t care what the words are. They just want to move to it. And that’s fine. But the art is, like, tricking people to dance. I guess that’s how I see the industry. But I do feel positive. I mean, someone like Macklemore being one of the most prominent people. . . he doesn’t have a label or whatever. He doesn’t rap super simple or in some corny way like other people do.

11: What do you hope people get out of listening to your music?

S: I don’t know. Whatever they want. When I make something, there’s something that, with all of my music, tickles me in a certain way. Even if it’s really simple, like a drum beat that you can nod your head to. . . but it pacifies you on a certain level, like a visceral level that you respond to. Some people are drawn to it. »

– Aaron Colter