“Birdman”, “Whiplash” & The Artist As Anti-Social Hero

In a moving and widely-circulated acceptance speech at last month’s Critic’s Choice Awards, Jessica Chastain cited her preferred definition of “MVP” as “a player who is valuable to their team.” Chastain deftly assumed the role of grateful recipient, first unspooling a string of shout-outs to her agent, lawyer, publicist, p.a., directors, and fellow cast and crew members, then delivering a succinct, unflinching plea regarding “our need to build the strength of diversity in our industry,” complete with a litany against “homophobic, sexist, misogynistic, anti-Semitic, and racist agendas,” an inspiring MLK quotation, and a rousing charge to “speak up” which even elicited a silent “Wow” from the ever-imperious Oprah. With her speech, Chastain presented herself as the premier socially-conscious artist, committed to cooperation, inclusivity, and mutual recognition.

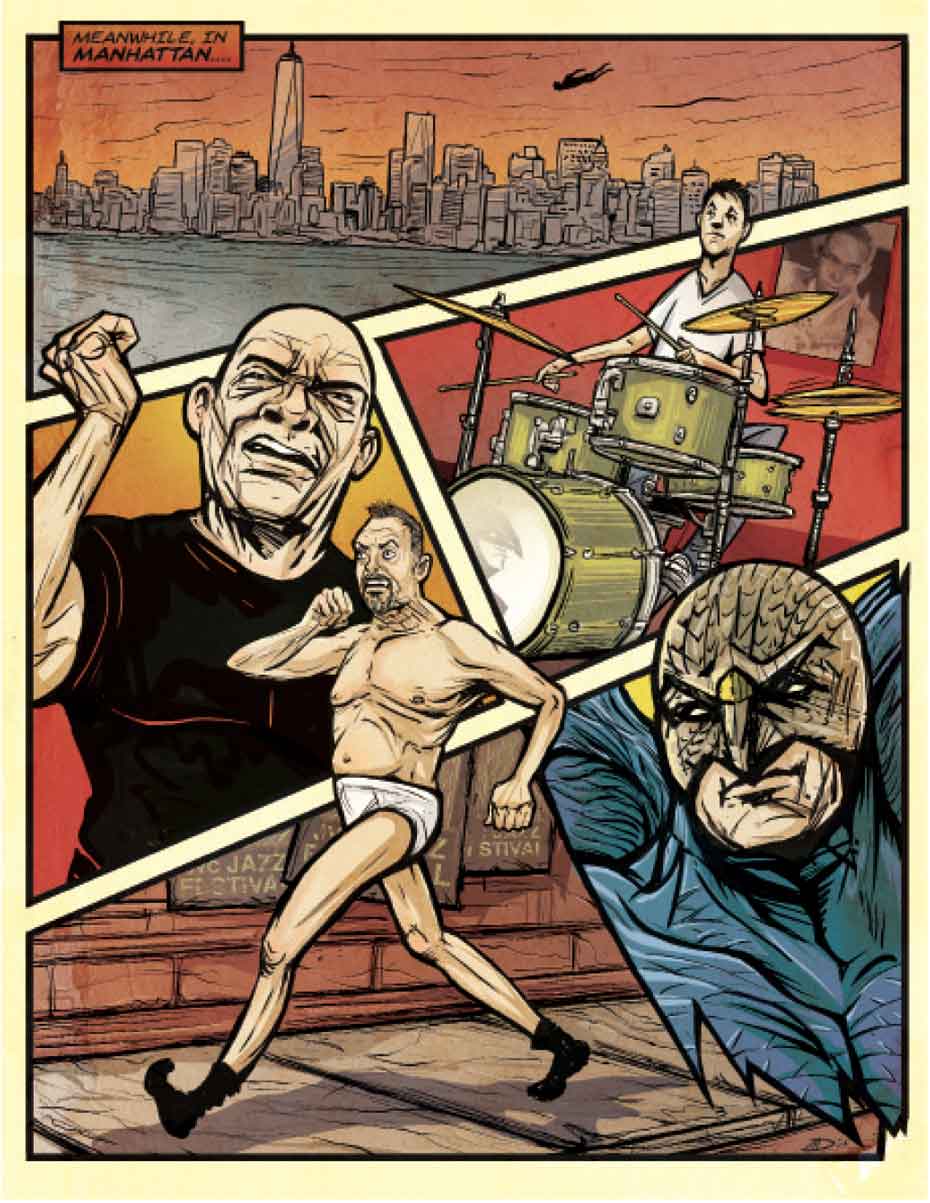

Two of this year’s best picture nominees champion a different model of the contemporary artist. Alejandro González Iñárrritu’s Birdman and Damien Chazelle’s Whiplash are paens to the performer as exemplar of American self-reliance. Birdman’s Riggan Thomson, played with Nicholsonian crustiness by Michael Keaton, is a Hollywood refugee struggling to garner critical legitimacy with a stilted Broadway adaptation of Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, all the while obliviously coasting on the laurels he mistakes for an albatross. Whiplash’s Andrew, limned with disarming sincerity by Miles Teller, is a fledging percussion student at the prestigious Schaffer Conservatory determined to win the approval of his sadistic conductor and ultimately secure a place in the annals of music history. Both of these brilliant, glittering fantasies of transcendence focus on men who embrace their true selves through devotion to their talents. These selves, however, happen to be radically antisocial and incurably self-destructive. By relentlessly pursuing the admiration of enemies and strangers, Riggan and Andrew willingly alienate their peers and intimates. Celebratory, but by no means romantic, these movies revel in the side-effects of American individualism: self-absorprtion, ostracism, and loneliness.

I walked out of these movies feeling elated, as though I’d been given carte blanche to indulge in the endemic myths on which I was weaned. For all of their propulsive, climactic energy, these movies have an intoxicating effect, navigating a path back to our national Mother Myth of unqualified exceptionalism. These narratives offer a delightful inversion of Nietzsche’s theory of the Apollonian-Dionysian tension that generates cultural production. In our enlightened era of critical theory, where the integrity of the subject has been ingeniously demystified, deconstructed, and all but dismantled by a slew of Marxist Freudo-intellectuals, the ego is the new id. Far from regressive fantasies of repressed beings eroding under the weight of the patriarchal superego and longing for a feminized chthonian swamp, where boundaries are blurred and hierarchies dissolved, these movies chart a vicarious return to a masculinized fantasy of sheer will generated by delusions of power founded on difference, competition, and an inflated sense of autonomy. It may not be the optimal mode of personhood for sustaining a functional, cohesive society, but it certainly makes for great cinema.

For Riggan and Andrew, art is not an end in itself, but rather a means of satisfying their own egos and achieving immortality. Both protagonists are embedded in communities that challenge these values, goading them to increasingly obsessive, antagonistic behavior. Throughout Birdman, we see Riggan assaulting his co-stars, confronting his critics, and trashing his dressing room in sporadic outbursts of rage. A string of heated encounters allude to a history of addiction, domestic abuse, and parental neglect. In a poignant scene, his ex-wife—numbed beyond affect, but unfailingly compassionate—informs him, “Just because I didn’t like that stupid comedy you did with Goldie Hawn does not mean that I didn’t love you,” adding that he always confused love with admiration. Similarly, his pugnacious daughter, played triumphantly against type by the immutably charming Emma Stone, launches an explosive jeremiad against his futile efforts to remain relevant in a world he willfully ignores. Though no one in the film explicitly sympathizes with Riggan’s myopic worldview, in private moments we see that the supporting players are equally susceptible to the lure of the deadly sins, from the pride of his leading lady and the lust of his nemesis, to the envy of his girlfriend and the wrath of his reviewer. The film’s inherent ambiguity is a refreshing change of pace from the tawdry universalism of the overrated Babel, and surely accounts for its more polarized critical reception.

Whiplash, on the other hand, is one of the least ambiguous indie films I’ve seen in recent years, and one of the best. Though modeled on the Bildung tradition, this narrative of a young man’s education proves to be a text-book Aristotelean development in which the ambitions set out in the beginning are ultimately realized. All seeming digressions into hidden motives, sentimental backstories, and sympathy-generating revelations are mere ruses for amplifying the movie’s final payoff. Whereas Birdman is dilatory and unresolved, Whiplash is rigorously controlled. With its watertight editing, each shot works to sustain the narrative’s claustrophobic tension. Even the film’s ostensible denouement, with its quiet epiphanies, is a cunning set-up for the final scene’s cruel, dazzling trick.

Birdman and Whiplash flirt with, and ultimately discard, the popular trope of salvation through intervention and reconciliation. Foregoing social integration, both films champion the transcendence of the Messianic entertainer. Despite radical stylistic discontinuities, these movies recall the ‘70s work of two American masters: Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller and Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon. Both films chart the rise and fall of men too arrogant to see the folly of their enterprising cruelty. Iñárritu and Chazelle trade the dour pessimism and existential sorrow of those New Wave masterpieces for a wry, cheerful cynicism. Birdman and Whiplash are two irreverent punk-rock entries in the tradition Robert Kolker famously described as “the cinema of loneliness.” Andrew and Riggan are anti-heroes for our strange neoliberal century, sublimely beyond saving by anyone but themselves. »

– Maxfield Fulton