Beer and Hugs: The Amanda Palmer Scandal, Revisited

Theatre is Evil

On stage at Boston’s Paradise Rock Club, hometown hero Amanda Palmer has just tackled guitarist Chad Raines to the ground. He continues to strum with frantic passion as she spreads his legs and makes her way between them. The sold out show’s audience squeezes and pushes closer to the stage to see if somebody is about to get naked. And just like that, Palmer’s newest single “Do It With A Rockstar” comes to an end.

“That’s what I pay them for,” Palmer jokes, readjusting her Klaus Nomi corset. “Actually I don’t pay them. They do it all for the exposure … I pay them in sexual favors.”

The audience brushes the joke off with a laugh. These are among the most die-hard fans Palmer has, in the town where she kicked off her career as half of “Brechtian Punk Cabaret” duo The Dresden Dolls. Elsewhere, however, the joke may have not gone over so well.

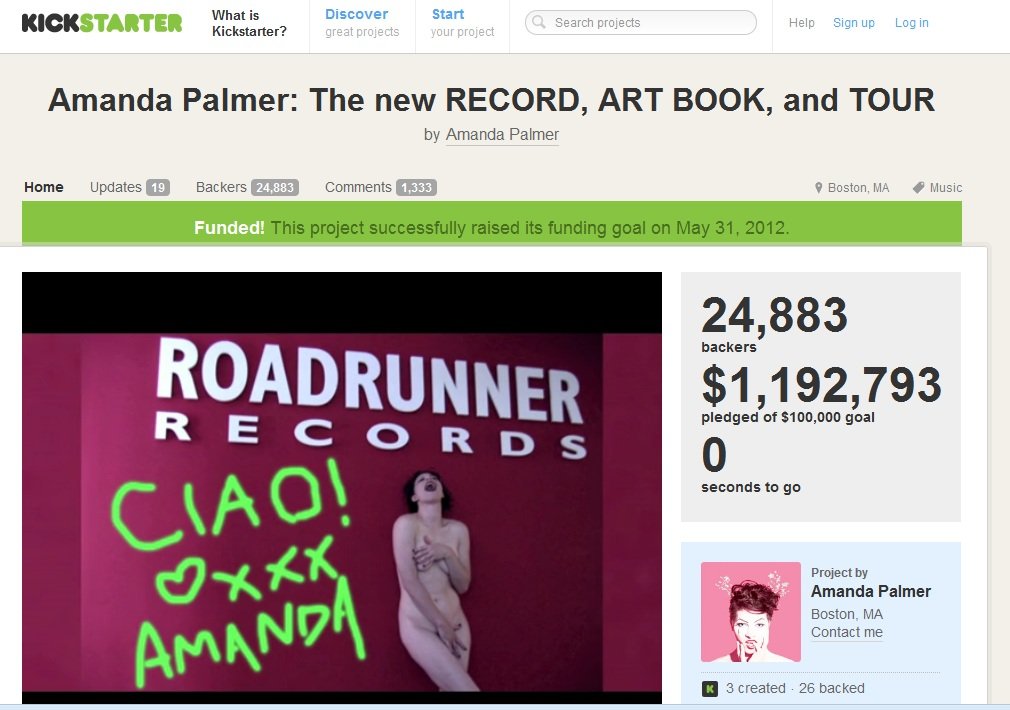

Palmer has attracted considerable controversy regarding the funding of her tour and most recent album, Theatre is Evil, which was released in September. After a successful fundraising campaign on crowdsourcing website Kickstarter, Palmer managed to raise almost $1.2 million in fan contributions, well beyond her $100,000 goal. She later outlined her plans for how to spend the money in a post on her Kickstarter blog. To date, it is the most successful Kickstarter campaign ever by a band or musician.

While comments on the post from backers were unanimously supportive, elsewhere on the Internet some began to question whether Palmer’s manufacturing costs (including $100 arts and crafts packages and $300 art books) were inflated. No backers, however, have come forward expressing dissatisfaction with what their pledges got them. On the contrary, many were ecstatic.

“Have you seen the packaging?” asked Robbie Simmons, an aspiring musician and producer who contributed $50 to the campaign. “It’s really really nice.”

- Simmons poses with his vinyl copy of Theatre is Evil

Simmons’ enthusiasm for Palmer’s work is palpable. In return for his contribution, he was one of 1,347 backers who received an exclusive deluxe vinyl copy of the album with artwork, thank you card and digital album download. Palmer, like almost all Kickstarter fundraisers, offered a plethora of other incentives to campaign backers.

For as little as one dollar, backers were guaranteed a digital copy of the album with exclusive backer-only bonus tracks. For $5,000, Palmer promised to come to the backer’s house to perform and throw a party. Thirty-four backers chose this option. The highest rewarded contribution, $10,000, guaranteed two contributors a one-on-one day with Palmer where she would serenade them on her ukulele, have dinner, and paint them on a large canvas, “naked or clothed.” VIP tickets to backer-only shows across the world were $300, and brought in more revenue than any pledge amount except $25, the most popular pledge across all Kickstarter projects.

“With most of the money, it was a pre-sale. It wasn’t a donation,” said Boston artist Katherine Bergeron, who recently launched a Kickstarter of her own to convert a 150-year-old firehouse into an art space. “A lot of people only paid a dollar for the record and it was only because other people were willing to pay a lot more that she was able to actually put out the record and go on tour.”

Ultimately, Palmer’s expenses for the project were accepted as justified by fans and didn’t become an issue until she was preparing to embark on her Theatre is Evil tour.

The “Grand Theft” Orchestra

Back onstage Palmer and the Grand Theft Orchestra begin the haunting introduction to the first Dresden Dolls song of the night: “Missed Me.” The crowd bursts into rapturous howls and applause. Two minutes later, the music stops and the four musicians stand motionless.

Palmer comes out from behind her piano and grabs Jherek Bischoff’s bass. Chad Raines tosses his guitar to Bischoff and takes his place at the piano. Michael McQuilken stays at the drums—for now. The song lasts eight minutes and doesn’t end until Palmer and company have each played all four instruments.

The Grand Theft Orchestra is a recent addition to Palmer’s milieu. When she toured from 2008 to 2010 with her solo debut Who Killed Amanda Palmer, she typically performed with significantly less accompaniment, playing many shows with only her piano, ukulele and raspy, tortured voice.

When Palmer began planning the Theatre is Evil tour, she instated Bischoff as her musical director. His job was to locate and recruit local string and horn players to perform with the Grand Theft Orchestra in each city of the tour. In addition, Bischoff would be in charge of rehearsals with the local string players and would in turn teach them to play along with his solo bass performance—one of the tour’s opening acts. According to Bischoff, this had been the plan long before the Kickstarter campaign went into effect.

“It was pretty apparent from the beginning that we weren’t gonna break even,” Raines said. “I was told from the beginning, before the actual American tour started, that we were playing shows where we would be hiring a four-piece string quartet section and a four-piece horn band—and then I was told that if we did that we would just lose tons of money.”

Several months later, as the tour was just beginning, the backlash began. In an open call for local string and horn players posted before the tour began, Palmer and the Grand Theft Orchestra promised to compensate with “beer, hi-fives and hugs” as well as eternal gratitude. The lack of monetary compensation offered in the wake of Palmer’s massive Kickstarter campaign income sparked a debate about artists’ rights among both fans and detractors of Palmer.

“We weren’t asking professional musicians who do this as a living to play with us,” Raines said, defending Palmer. “We didn’t expect a lot of those caliber musicians. We expected friends and fans to play.”

Chicago musician and music journalist Steve Albini, who Palmer had cited and praised in her initial post detailing her finances, notoriously wrote on a message board, “Pretty much everybody on earth has a threshold for how much to indulge an idiot who doesn’t know how to conduct herself, and I think Ms. Palmer has found her audience’s threshold.” Headlines soon started appearing along the lines of Sterogum’s “Steve Albini: Amanda Palmer is an Idiot.”

“At the time when the New York Times was publishing articles saying Amanda doesn’t pay her musicians, it just wasn’t true,” Raines said. “I’m getting paid, and no one even called me and asked me what the actual situation was.”

Albini later apologized for his remarks in a post on the same Electrical Audio message board, acknowledging that he did not believe Palmer was an idiot and was not particularly familiar with her work. He followed that, however, with, “But still it should be obvious also that having gotten over a million dollars from such an effort that it is just plain rude to ask for further indulgences from your audience, like playing in your backing band for free.”

Bischoff quickly came to Palmer’s defense in a blog post where he took most of the responsibility for the backlash. “Part of the reason there was such confusion surrounding crowdsourcing musicians is because it wasn’t happening in every city,” Bischoff wrote on his website. “From the beginning, Amanda and I were approaching assembling extra players in different ways. For her, it really was all about engaging her fanbase, and her belief that it would be an exciting and unique way to involve her fans, that would add yet another element of intimacy to each show.”

Bischoff claims that certain shows did indeed have a budget for backing musicians while others did not. Following the backlash, Bischoff promised to offer compensation in any way he could through sales of his merchandise. Palmer promised to pay all of the musicians, including retroactive payments to those who had already performed for free on the tour.

“Getting a hundred dollars for the show was like an extra bonus they weren’t expecting,” Raines said.

The Future of Music?

When Palmer’s sordid ditty about falling in love with one’s child molester comes to an end, she and the band play the other two singles off the new album, starting with “The Killing Type.” After wrapping up what would become Theatre is Evil‘s next single, “Want it Back,” Palmer addresses the audience.

“A lot of you probably donated to our Kickstarter,” she says. Hordes of audience members cheer and salute the stage to confirm their involvement. “You helped make this happen.”

Palmer has repeatedly stated that she believes Kickstarter and similar crowdsourcing platforms are the “future of music.” Her enthusiasm for independent funding can in part be attributed to her tumultuous relationship with major label Roadrunner Records.

Following the 2008 release of Who Killed Amanda Palmer, Roadrunner wanted to remove shots of Palmer’s exposed midriff from her “Leeds United” video. While the label had no issue with Palmer’s perpetually unshaven legs and armpits, they said she had too much belly fat. Livid, Palmer took to the Internet and started a “rebellyon” protest in hopes of getting kicked off the label. Thousands of fans posted belly shots of solidarity, and Palmer was released from her contract. As a farewell to Roadrunner, Palmer blogged a nude photo of herself cackling in the lobby of their German office.

“The future of music? No,” Simmons stated bluntly. “The future of independent music? Maybe. I think to have that kind of success with Kickstarter you not only need to have a devoted fanbase, but you need to be the kind of person who’s involved at every step of the musical process. Someone like Carly Rae Jepsen can make it to the top of the billboard charts, but not without a whole team of writers, producers and promoters to back her up and turn her into a marketable product. With someone like Amanda Palmer you know that the product you’re putting your money towards in advance will be her artistic vision.”

While Palmer’s control of her finances has afforded her more artistic freedom, it is not without its downsides. “Even on the road now she couldn’t quit,” said Bergeron. “Even though she had bronchitis at the end of her tour, she couldn’t back out of any of her gigs without losing significant amounts of money.”

Palmer has volunteered to perform at an end of the year gala party for donors to Bergeron’s Kickstarter campaign, which earned more than twice its initial $10,000 goal.

To date, Palmer has backed twenty-six projects on Kickstarter. Of those, only two have not been funded successfully, a low number considering that only about 44 percent of Kickstarter projects attain funding. Since the initial campaign, Palmer has launched two more. The first funded a performance tour with her husband, bestselling author Neil Gaiman, which raised more than 666 percent of its initial $20,000 goal. The second funded an EP for one of Palmer’s latest proteges, Tristan Allen, raising $8,581 with a goal of $3,300.

Palmer’s representatives have declined an invitation to comment, citing the artist’s health.