Jenny Forrester

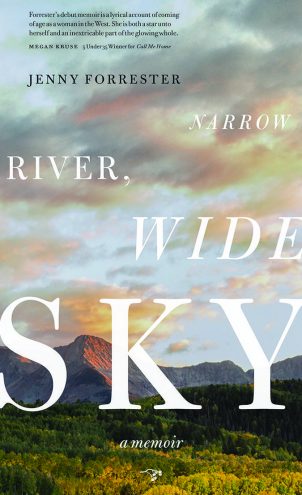

Memoirs can be tricky. Sometimes the author can conveniently leave out details that are either too embarrassing or too emotionally charged to dredge up and expose to the world. Jenny Forrester is fearless in how she tells her life story in Narrow River, Wide Sky, where she deftly weaves layer upon layer of experience to create a story that mirrors the physical surroundings of her Colorado home. It’s a fiercely honest American story of a family fraught with the challenges of adhering to a value system that sometimes fails them, while dealing with the ebbs and flows of their ever-changing relationships with each other. And while Forrester’s book is a memoir, her style makes it feel like a novel.

I met with Forrester before the latest installment of the Unchaste Readers Series at Literary Arts, downtown. She was anticipating the night’s readers including Melika Belhaj, who wanted to share her thoughts about the horrific stabbing on the Max train a few months back. Forrester has been curating the event for five years now, and was beaming with positivity about the series that provides both a platform and a community for women writers in Portland.

ELEVEN: Even for a memoir, you have documented so much of your life in this book. Did you always keep a diary, or have you based a lot of this off your memory, or is it a combination of both?

Jenny Forrester: I definitely kept a diary. My mom gave me one for Christmas. It was a five year diary so it has a lot of history in it. It’s super repetitive as a life is. I actually took notes of what I did in the morning: I read my bible, I read Forward Magazine, which was the Episcopalian little booklet. So it was very redundant, yet there are these tiny little shifts that I can see from my adult perspective that let me know that one, I do remember things better than some people say that I can, so I really trust memory. There’s a lot of controversy around that, but I believe in it. The other thing is that I can take from my diary little snippets or little phrases that document my documentation.

11: A lot of people write a thinly veiled version of their own life and just use different names. Your book is a memoir, but it reads like a novel; the story of your mother, your brother and yourself. Can you talk about the dichotomy between you and your mother and brother after your father left?

JF: I always felt like the third wheel when we became three people. That happens a lot with triangles. If there are three children one will feel left out. It’s a human dynamic. They were always the adventurous people and I was always the one afraid that we were going to die somewhere. They also dreamed the same dreams. I documented one in particular, but they did that on a regular basis. So they had a real connection that I felt I was missing because I was more bookish and sedate.

11: You were the sensitive one. The thing that struck me is how much animal killing you had to deal with on a daily basis. How did you deal with this?

JF: When baby goats are born, they are very cute and you become attached. Some of them are males and you’re not going to keep the males, because we didn’t have that kind of a goat herding operation. So they went away and we knew where they were going. The animal part of our lives was rich with life and death. For me, I think it was better that I was sensitive. I don’t know if that make sense, but I have this sense that if you turn that off you can turn a lot of other things off. So I appreciate that everything makes me cry. That everything did make me cry and that everything is always going to. It’s not going to stop and that I’m going to grow along those lines, even now. Someone just the other day called me a princess if you can believe it. I’m older now and I’m still being called that. The person who said that was not a cowboy, she was just a Portland liberal. It’s interesting that toughness is something that we value regardless of our political ideology.

11: Speaking of politics, can you discuss the difference between you and your brother in that regard?

JF: We went to church all our lives. We believed in God and became more and more devout. I became more devout and religious and the Rainbow Girls had a lot to do with that. The study of true womanhood was about the women’s place in the patriarchy.

11: I’m not sure if I understand that scene where you were swept away in the middle of the night to go to a Rainbow Girls ceremony.

JF: It is a strange scene! I wanted to put it in there because not a lot of people even know about the Rainbow Girls. Even in places that know a lot about feminist theory. They’re out of the Masonic Lodge. When you grow up, you’re an Eastern Star, as a woman.

11: I usually don’t ask about the title, but Narrow River, Wide Sky, there’s a lot going on there.

11: I usually don’t ask about the title, but Narrow River, Wide Sky, there’s a lot going on there.

JF: There’s multiple things. In the beginning, I called it A Trailer Trash Republican Childhood, but that probably wasn’t the best title. Then I called it Children of a Narrow River, but the word children is not always good for appeal. So then we were looking at landscape, I put it out to my writers group, and I put it out to other friends as well. Ron, my husband, said, “What do you all think? Give me some images.” So from that, the narrow river is the path you can have in life. This is the way you can think about life, this is how you can react to tragedy. When I get to Portland, and the river widens to where I can actually consider other philosophies, it doesn’t mean I am a terrible person. I can think about life in a wider way, and that I want to think in a wider way.

The other part is that there is this possibility. My brother and I had a particular life. We had a particular set of expectations and possibilities. And now being an adult and having the opportunities that I’ve had, I can have a wider range of opportunities and possibilities. Motherhood was part of that wider river. Because my daughter came home [from school] and explained some things to me about gender that I hadn’t considered. They’re new. New not as far as meaning, but new in how we talk about it. She went to The Metropolitan Learning Center and had this information and she shared it with me, and it blew my mind.

11: Can we talk a little about losing your mother at an early age, and how that affected you as a mother?

JF: I think because I had my mother as a mother for a very short period of time, her words “You can do this” and “Listen to your heart” and “Do what you think is right” are so much more powerful than if we would have lived our whole lives together. They are the gems that I got from her. If we had a longer relationship, who knows what would have stuck in my brain. As a mother, her influence was very great, and weighted heavily, even though I had her for a short time. Or maybe because I had her for a short time.

11: I love the term, “Pioneer ghosts.” Can you talk about that?

JF: I wanted to talk about gentrification without using the word gentrification. People think gentrification is only a city thing, or a suburban thing. If we want to talk about gentrification we can go all the way back to 1492, and we should. Because all of these waves cause a destruction of the people. As we know from our history, our pioneer settler mythology of America keeps us all to some extent, but especially white people sort of like what Ta-Nehisi Coates calls “The Dream.” This pioneer mythology was part of our growing up and it was in our schools’ curriculum.

11: Tell me about the Unchaste Reading Series. How did it get started?

JF: It started when I heard one too many rapey poems at a bar and I thought, why am I doing this? Why can’t we have all women? How does it change the content? How does it change how we do readings, the way that we talk about literature? Why not try this big experiment, and also poetry, and you know, booze? It was going to be quarterly, and pretty soon it was every two months and now it’s monthly. I try to make sure there’s lots of ages and ethnicities and genders now. So now, it’s only if you’re not a man.

11: So now you’re going back to the definitions from your daughter. It has come full circle.

JF: “I was very proud of myself,” I said look at this reading series. And she said “Mom, I have to tell you something. You’re not doing it right.”