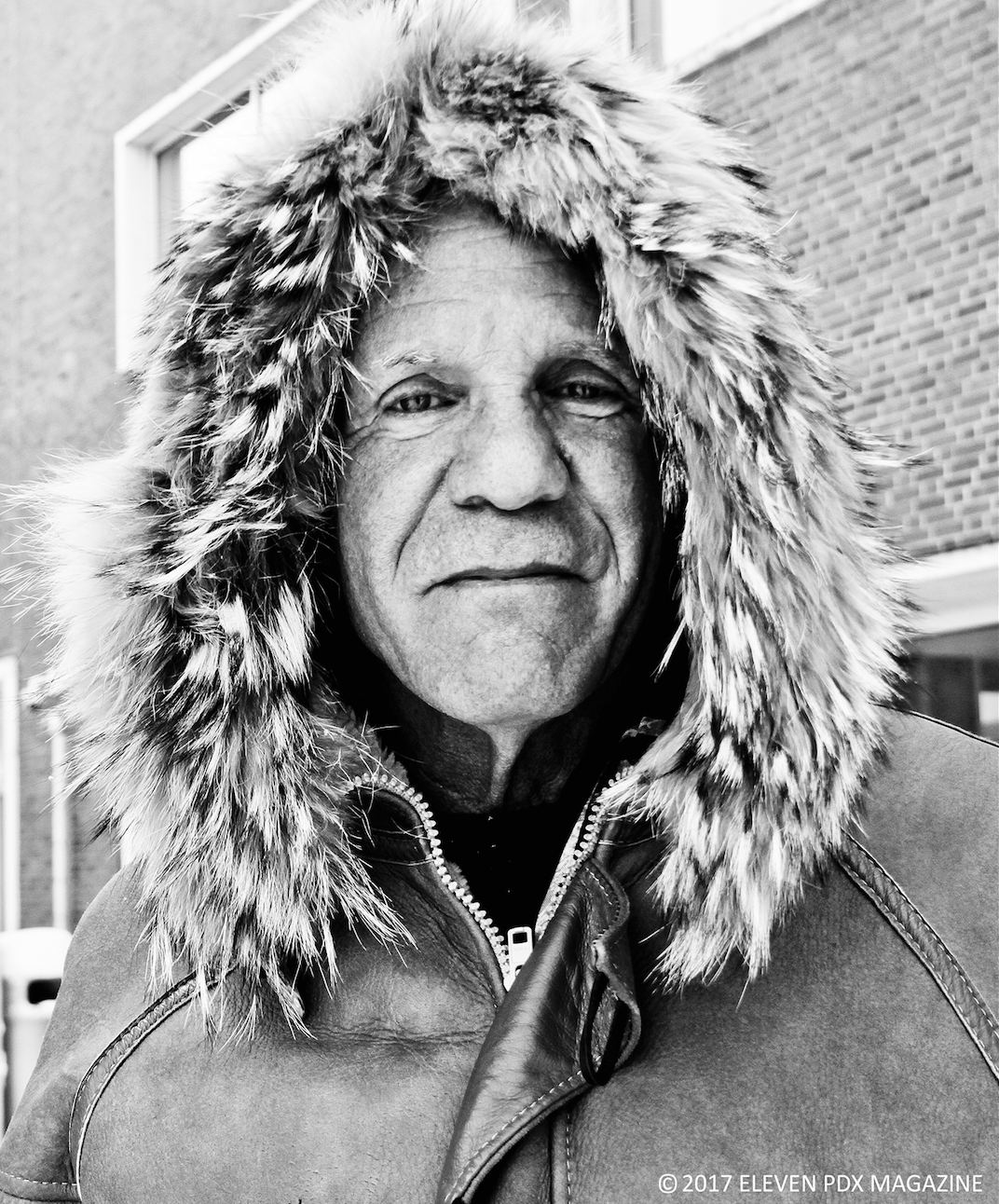

Portland writer and broadcaster Jim Newman

From 1975 to 1989, anyone who tuned into the CBS affiliate WCCO-TV in Minneapolis saw Jim Newman delivering hard news with refreshing honesty in a time when entertainment stories started to drive ratings. Eventually, the ratings-over-facts approach in television newsrooms began to erode Newman’s enchantment with broadcast television, and in 1989 he returned to his home state of Oregon to become “The Voice” of Oregon Public Broadcasting’s (OPB) Oregon Field Guide. For 20 years and 250 episodes, Newman covered the majestic landscapes of Oregon, until he departed from OPB in 2009.

These days, Newman is a Portland journalist-cum-novelist whose long career in television news and script-writing informs the fiction he writes. His first book, A Habit of Mind (North Star Press, 2015), gives readers a satirical look into the newsroom, using many of the same Shakespearean comic elements employed by the Coen Brothers. It’s an oddly prescient book that anticipates the current obsession with fake news, while also commenting on the media’s responsibility to report stories with honesty. Newman is currently busy putting the final touches on a new book called Visible Light that satirizes the U.S. Army. Visible Light will be the second book of a developing trilogy.

Eleven: You have a long history in journalism, dating back to the 1970s. Can we begin by talking about your career as a television writer?

Jim Newman: I started working at a Minneapolis station called WCCO-TV in 1975 when Knight Ridder owned it. The job — I worked there for 15 years — was beautiful. It had a great reputation because of its journalistic integrity through the leadership of Mr. Ridder, who actually visited our newsroom often. When he did, people would salute him, and I always thought everyone was sucking up to him at the time. But it was only later I realized that he was the guy footing the bill for us to not worry about ratings, or how expensive it was to produce the news. He was the guy who made it possible for us to be real journalists.

11: From a journalistic perspective, this was at a time when the newsroom changed tremendously. Can you discuss witnessing the shift toward ratings-driven entertainment news, and away from hard news reporting?

JN: Television journalism degraded in a severe way while I was there. The original premise in the newsroom was: “We don’t care about the cost. All we care about is the news and the facts.” But nationally, television stations started to realize that news can draw in ratings, and producers began to face the true cost of news production. Once the potential for profit was apparent to management, profits became the central focus for those at the top. After that, the news business changed tremendously. WCCO eventually went through a real crisis, even though we believed ourselves—and we were—the television news source of record. Whatever we said on the air, that was true and detailed.

11: And you went on to work for Oregon Public Broadcasting on “Oregon Field Guide.” How was your experience working with them?

JN: I was made for working with OPB. I got to go up mountains, and I saw places in far eastern Oregon I wouldn’t have seen otherwise. And as a writer and a reporter, working on “Oregon Field Guide” was great because it was magazine-style programming where we did seven-to-10 minute stories. This format allowed us to delve deeper into all kinds of stories about aquatic life, volcanism, and the landscapes themselves. A big element of that reporting was capturing the landscape, or the research happening on that landscape, by traveling the state.

For example, we did a story on the appeal of an ice age meadow. It looked like simple farmland to us from a distance, but as we walked into it, we found that it had its own surreal beauty to it, which we got to experience. There’s another place with a boring name called Leslie Gulch that is the remains of a super volcano, which is perhaps the size of Switzerland. Now, after millions of years of erosion, it’s sculpted into these cliffs and formations that are absolutely stunning. It’s one of the most spectacular places in Oregon we visited.

11: You’ve since stepped away from journalism in 2009, and you’ve dedicated much of your time to writing fiction. Can you talk about how you transitioned away from journalism and into becoming a novelist?

JN: When I left OPB and stopped writing television scripts in 2009, I tried to write fiction that was straight-ahead and non-ironic, because that’s what I knew from writing on television. But I’ve found that when you have a lifetime of experiences, one beautiful way to engage with those experiences is to put them on paper in some form—even if it’s just fiction, which is informed by what’s happened to me over time. But it seems to me that my younger years from 20-45 were years dedicated to recording the experiences I’ve had, and what I’ve gotten is a library of data that I use for writing.

I have this other added advantage of tapping into my subconscious that allows me to be more open, so one of the big motivations for writing is to learn consciously what I know subconsciously; kind of like a guide standing there telling me, “When this happened, it actually meant this.” All I am doing is unfolding it through the eyes of these fictions, aided by my subconscious, informing me what this stuff means.

11: One of those things is a novel you released in 2015 called A Habit of Mind, which satirizes the media. How was A Habit of Mind informed by your time as a journalist?

JN: A Habit of Mind is certainly an attack on the financial architecture of the news industry, and how it degraded the accuracy and detail of television reporting. I also wanted to comment on how the media contributed to a dumbed-down public, who was flattered by how television presented itself in the way that leads people to believe that they were getting what they needed to know from the news. Instead, what we get is a diluted information stream that everybody needs, which I was trying to bring attention to in that book.

11: It’s oddly topical, considering the media landscape of today. Was there a conscious attempt to draw attention toward what is now being labeled as “fake news”?

JN: That was my primary concern in A Habit of Mind, which was to explain fake news through satire. Strangely, when I wrote that book in 2015, I thought of it as being over the top, but in 2017 it feels like I was right on with that perspective. But that is very much the subject of A Habit of Mind, and I think it’s important because this degradation of news with a diminishment of any concern for the facts is being played out in real life with Donald Trump, who has essentially created his own reality. Neither the news business nor the public seems to have the authority to put things back on track and say, “Wait a minute; there are things such as the truth here.” But my hope now is that the treatment of media will incite some sort of renewal in the agency of the newsroom by journalists who are seeing this stuff happen.

11: I saw that you are finishing up a novel that focuses on the U.S. Army. How is that going?

JN: In Visible Light, a book I’ve recently finished, I am directing my attention toward people in the army who find a way to survive even though their limitations suggest they are unfit for the positions they hold. The main character, Tad, is essentially an honest person, but he’s willing to cut corners. He’s in a world where he is confronted by people who are very smart and honest, and other people who are looking for an edge that will get them ahead. But instead of focusing on the media, I am directing my attention on the army this time. I also have a third book about Vietnam that I am working on, and I like to think of those three as a trilogy.

11: How do each of your books relate to one another as a trilogy?

JN: In A Habit of Mind, the main character is some guy in his twenties that satirizes the newsroom, where I spent most of my time. He’s wrong about a lot of things, and he makes mistakes, but the context of those mistakes is correct, and he’s just living it, only he’s not aware of what’s happening. The book I just finished, Visible Light, is also about a young guy who is inexperienced, but that world, along with the people in it, are a part of a landscape of my younger years from when I was in the military. My third book, Words from the Front, [is] about a time [of] some real trauma and conflict in my life: partly because of my sexuality, and when I was trying to make sense of what all of that meant when I was coming out, while also talking about an alcoholic father and what that’s like for the kid in the book.

Those three books are about young men trapped in a world that they never made, who are trying to make sense of their worlds as they make all kinds of dumb-ass mistakes. But whether I’m making a satire out of the media or the military, these books are about being set free.»

– Morgan Nicholson