Portland writer Kait Heacock

Writing about family often provokes readers to wonder if what we are reading is, in fact, autobiographical. It’s an unfair imposition we make so that peering into the personal lives of fictional families can satiate our own voyeuristic hunger, even if we know we are doing away with the concepts of Barthes.

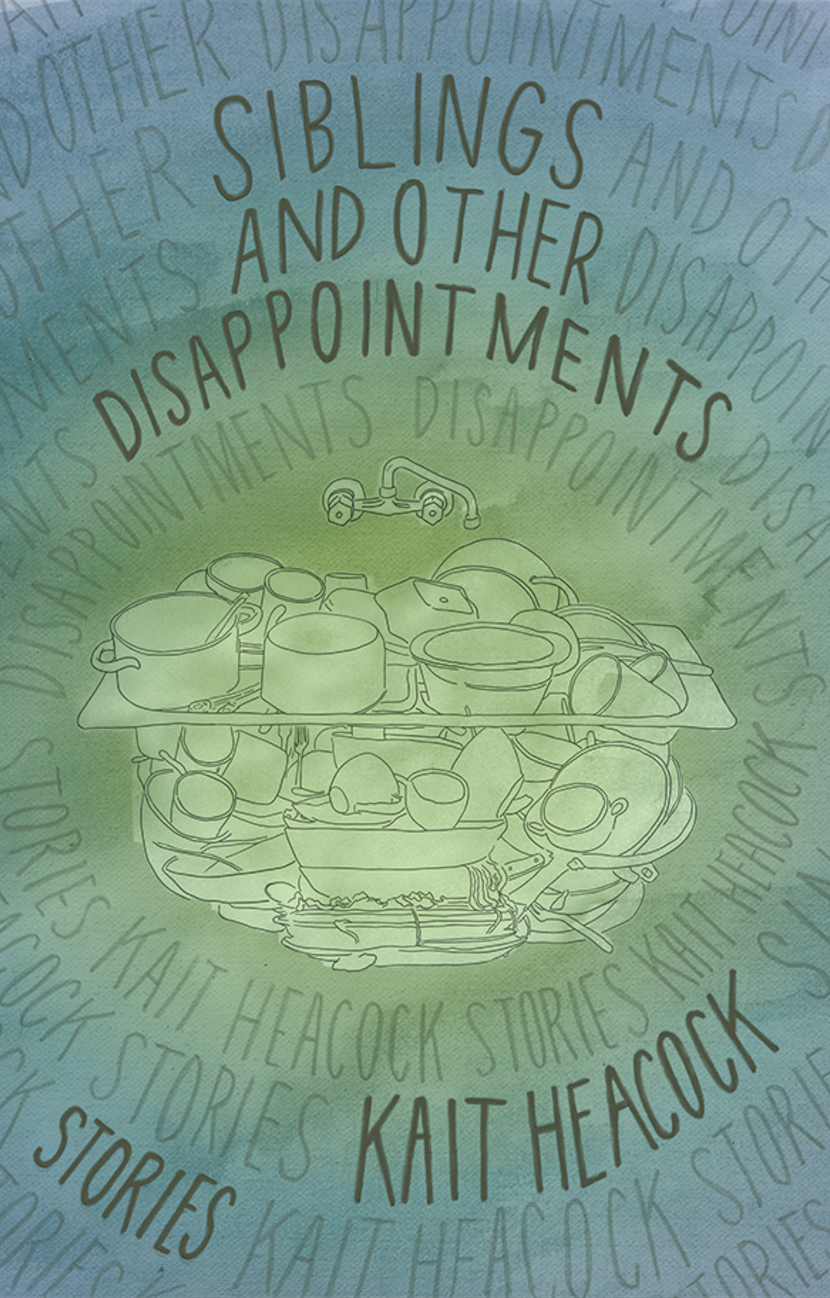

Kait Heacock is more aware of this now that her debut collection of short stories, Siblings and Other Disappointments (Ooligan Press, 2016), is in the hands of the public and her own family. But make no mistake: The Siblings collection isn’t an autobiography titled What We Talk About When We Talk About Kait Heacock, even if that does have a nice ring to it. Instead, Heacock’s acute examinations of family stand on their own as a wonderful collection of regional fiction that’s covered in the dirty realism of Raymond Carver and cleansed by the rainwater of the Pacific Northwest.

Eleven: Let’s begin by talking about regionalism. Can you tell us about how Siblings and Other Disappointments relates to the Pacific Northwest?

Kait Heacock: Setting has always been important to my writing. Especially in Siblings and Other Disappointments, because I am trying to place myself in this genre of dirty realism, while also positioning myself as a regionalist writer in The Northwest. Writers like Anthony Doer, Rick Bass, or Richard Ford, who had a collection called Rock Springs that takes place in Montana, each inspired my writing. But even as I say those names, I realize that a lot of the writers associated with the Northwest are men, who wrote these blue-collared short stories, which is perhaps one reason why I am drawn to writing about men in the Northwest.

11: You are a feminist writer who successfully writes from the male perspective in a masculine way. What drew you into writing about men the way you did in this collection?

KH: I write about men because I am female, and I’ve felt that I couldn’t be a part of the worlds I saw my dad in, who worked in the auto industry, or my brother, who worked on a fishing boat in Alaska, or my grandpa, who drives a semi-truck. These are mostly male dominated worlds, and they fascinate me because of their camaraderie, so I want to know what those worlds are like. That’s why I wrote about a truck driver and a fisherman, or a gambling addict, because I wanted to peek into these secret worlds of men. I also wanted them to be in the Pacific Northwest because I wanted to contribute to literature that represents where I am from, as sort of a love letter to the small towns I’ve grown up in.

11: One of those small towns is Yakima, Washington. Can you speak about how your hometown shaped your experiences as a writer?

KH: When I was growing up in Yakima, a lot of my dreams back home were of escaping my small town. Wanting to go to New York, being a writer, and being all those things that girls like me dream of doing. When I got out and went to college, I hated going back and visiting my hometown. It felt very raw to me. But as time went on, I had more experiences, and I started to appreciate my small town.

The Northwest was especially relevant when my brother passed. I came back for a month, I quit my job, and I lived at my parents’ house, and I was very much on a brink of becoming a townie and living in Yakima. I went out to the same bar repeatedly, befriending friends from high school. I thought I’d come back and live there. But I went back to New York and I kept writing. I kept writing because that was the one thing that could bring me home, back to my childhood, and back to my brother. But so far, writing has been a vessel for me to not only think about where I am from, but to honor it, and to also poke fun [at] it, because I am from the there.

11: Raymond Carver also grew up in Yakima, which must have been inspiring.

KH: It’s no surprise that the biggest influence on me, especially on Siblings and Other Disappointments, is Raymond Carver. I came late to him, which is funny because of where I grew up. But once I discovered that fact, Carver became this personally important writer to me. He was the writer who made it possible for me to understand my brother, who was also an alcoholic, like Carver. Knowing that, Carver became my lens into this “broken manhood” that I saw in my brother, that I couldn’t talk about or process. Even down to the various stories that cover Alaska, which is where my brother was when he passed away a few years ago.

But whenever I tell people I like Carver they are like “oh yeah, whatever,” but sometimes I worry it’s because Carver is someone I should say [I like] because I am a short story writer, and because I am from the Northwest. But it’s always been so much more personal than that. I also think a lot of those ideas about broken family were also things that Carver wrote on, which are also seen in my writing. My stories are about dissecting different family relationships, with every broken form these relationships take on, as well as being about the families we are stuck with, or the families that we didn’t choose, or the ones we did. But I don’t think I am the next Raymond Carver, but I’d certainly accept being the next female Raymond Carver.

11: Since you’ve left Yakima, you’ve moved to Seattle, Portland, and Brooklyn, but you’ve recently returned to the Northwest. Did the Siblings collection change through those transitional periods? Or did you manage to maintain the same vision throughout the writing process from beginning to end?

KH: I was writing the stories in this book over a timespan of five years. I wrote most of them in Seattle and Portland. The last story I wrote — I needed some time to process that one, because it was based on some real stuff — I wrote in New York. I haven’t written about New York yet, and so far, all my books have been set in either Seattle or Portland, and places around those cities. I tend to write about places after I leave them.

The Siblings collection started out as a bunch of short stories I wrote after college. I think what affected them the most was the editing process, when all the bigger changes began to happen during the life of the book. It was also during the editing process when I lost my brother, so that profoundly affected the final story in the collection, which also affected the title, which then affected the tone of the book. Since finishing this collection, I’ve written a dozen or so other stories, and I now look at those as being a manuscript for a collection. The new stories I’ve written are all about female sexuality, because I got tired of writing about old drunk dudes, so now I am now writing about women having sex.

11: You have also been heavily involved in the literary communities of each city. Can you talk about the experiences you’ve had in Northwest literary communities?

KH: The first community I got to see was Seattle’s. And I saw it as a shy college student, at a point when I didn’t have the confidence to insert myself into the literary scene. It’s a small scene, but there are five or ten authors who will probably be at an event you go to. Some of these people are huge, like Sherman Alexie and Maria Semple — these cool people who are a part of the Seattle literary community who make it awesome.

When I went to Portland, which might be smaller, I found it so fucking cool. There are these house readings, and reading at those makes you feel like a famous musician or something. There is also a cool scene centered on Tin House, and they throw the best parties, which I went to before I read at Wordstock. But Portland also has tons of other great small presses that are very supportive in the community. And there are writer’s groups like Lidia Yuknavitch’s, who hosts these very talented and well published women, and they continue to meet up and attend each other’s readings all the time. The Portland community is just very supportive.

11: Speaking of support, how has your family taken this collection?

KH: I am always getting relatives who want to buy the book, and they are asking if this is a memoir, or if it’s about my own family. I know that even if it’s fiction, people will speculate if any of the stories are real. But my family has been nothing but supportive of the book — especially knowing that they are going out on a limb for me as I put fiction about family into the world.

11: Now that you are done with Siblings, have you experienced any moments of achievement through the writing process since the collection’s release?

KH: One of the moments that comes to mind is when I was hanging out with my 13-year-old nephew, Elias, who I think is the coolest kid in the world. He thinks I’m still kind of cool, but he doesn’t want to talk to me anymore because he’s a moody teenager. Anyway, we were hanging out, and I handed him a copy of my book, and when saw his name in the acknowledgements page, his face lit up. It was just such a cool moment.

But I think the most meaningful moment so far was a couple weeks ago when my sister-in-law, who was married to my brother, sent me a text message telling me, “Your brother would have been very proud of you.” Writing is my way of talking to my brother, but my book came out a little too late, so he never got to read it. But it’s still my way to keep the conversation going.»

– Morgan Nicholson