Portland Writer Luke B. Goebel

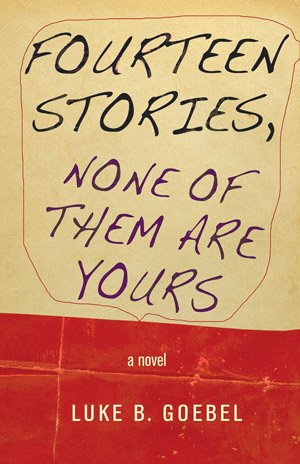

His debut novel, Fourteen Stories, None of Them Are Yours starts out with our narrator on a hospital bed, being treated for pancreatitis and suffering from a shattered relationship: “I can take the body’s betrayal at first, I think, but I think of Catherine and I’m done for, nearly.” He also has recently lost his brother, but it is not talked about much early on, other than as a point of reference to the story being told as “before” or “after” Carl. Luke has already received high praise for the book, being compared to the likes of Kerouac and Kesey, and winning the Ronald Sukenick Prize for Innovative Fiction. When asked if his his book was written in a stream of consciousness like On the Road, He is quick to object. “It’s conscious, not streaming. . . it’s choosing.” And he’s right about that. He writes with a fractured consciousness that’s perfect for today’s ADD audience. At first glance, you may think Fourteen Stories is just the musings of someone who has seen the other side of sanity and is working his way back through a maze of heartbreak, loss, and longing—“A feeling ride,” as he calls it. But there is much more to it. The reader experiences the tightrope the narrator is balancing on.

Fourteen Stories is a wonderful mess of a book, alive in all its manic glory. The frenetic stories are only heightened by the cadence in which he spills his guts across the page. The narrator speaks to you parenthetically for a while, with a funny story, then goes back to the desert and peyote with Indians. The voice is so present that you feel like you’re riding shotgun in some endless trip across America, listening to his wide-eyed tales of madness, jealous rage, and sex. Luke is very modest about his work. And therapeutic as it may have been for him to write it, he’s also a master of craft and language. He was recently back home in Portland, for his book release at Powell’s on Hawthorne, accompanied by his pup Jewely (who he had rescued from a kill shelter) only to return to his students at the University of Texas at Tyler the very next day. I was fortunate to spend some time with him at Loretta Jean’s, where we ate apple pie and talked about his book and his life.

ELEVEN: So first off, do you consider this an autobiographical novel?

Luke B. Goebel: I would say no. To me, an autobiographical novel is very close to memoir, a thinly veiled memoir. I don’t think my book is that. Are there things that are true? Sure. But I think the difference is that I shattered the back story a long time ago. If you have to take the whole story of your life, whole hog, and just veil it, then maybe that’s an autobiographical novel. What I did was shatter my identity, my attachment to this place, my people, the idea that this is my story, and it’s too precious to abandon. I just smashed the fuckin thing and took pieces. And then said, “What if I take this piece and that piece and make this part up?” And then there’s just messing around, making up the story of America, playing with context, playing with ideas, creating a dialogue between myself and the text, myself and the reader—to keep them thrilled. I wanted to give them something honest and true and also bigger than just myself. I don’t want to just drag someone by the hair through my life. I want to give them their life. It’s just universal. So is it autobiographical? No. Is it true? Yes. Is it factual? No. Partly? Yes.

11: Do you feel you have more responsibility to yourself or the reader to tell your story?

LBG: All of the above—to myself, to the love that I’m describing, the person in my life that I’m writing about, Catherine, to everyone in the hospital, to everyone who’s ever been in a hospital, to everyone who will die in a hospital. . . you know, all of it. It’s not like I have this big burden of responsibility or I have to save the world, it’s just. . . what is this thing that I am feeling? What am I experiencing? Why does a hospital feel so true? Because we can’t get out of it. We’re born and die in these things. So it’s like, how does that speak to us?

11: These are all very human stories, and seem very timeless. Like when your character is held up at gunpoint in Puerto Rico and the thief is crying. The desperation in it feels like it could happen at any time.

LBG: Yes! Before guns it was something else. First of all, that did happen. The guy really did hold me up, and he really cried, and he really gave me a cigarette, and I made him light it. I thought about hitting him, but I only had twenty bucks on me, so what’s the point? I gave him the twenty and he gave me this great fucking story, and this memory, and his heart, him just weeping, all drugged out. Just a beautiful guy. He wanted to tell me how friendly the island is, in Spanish, and he was really apologetic about not welcoming me properly [laughing]. At least it was a 45 caliber, which is what I like to shoot out in the desert out here in central Oregon. If he held me up with a 22 I would have been kind of insulted. I’m sorry. . . what was the question?

11: Just for you to talk about the human aspect of these stories. It doesn’t seem like you were out to write the “Great American Novel” here. They just seem like stories of connection.

LBG: Everyone wants to ask you these questions. Everyone is now an academic. I’m an academic, i.e. I teach, which is absurd for my life story. You write the thing, and then to be able to speak about it in this really intellectual and academic way—we have all these great theories, and it’s wonderful. But in truth and what I really wanted to say is that I just don’t really know. You don’t ask an actor how they do it. It’s just acting. We all talk a lot about what we do as writers, but basically I have a lot of attention to sound, to sentence, and from studying with Gordon Lish, I pay a lot of attention to recursion. I understand the game of really grown-up peek-a-boo. You start something, then abandon it for a minute and then bring it back. That keeps a sense of the familiar. There’s a sense of order. You can do that with craft, sound, themes, and stories. So I understand what I’m doing and what I’m playing with. But what it really comes down to is that I didn’t have a plan. I wasn’t writing this kind of novel or that kind of novel. It was just these accidents that turned into stories. Like buying an RV and driving across the country and weaving them together after I already had the book deal. I wanted to keep going. I still wanted to talk about my brother. I still want to talk about my life. I wanted to see how these things connect. I was playing the game, but had something urgent—I wasn’t done talking.

11: Where do you think modern fiction is going? It doesn’t seem like people are reading as much as they used to.

LBG: I read an article that the millennial kids are reading more than any other generation for decades, so people are reading. I don’t know if anything is as good as it used to be. A few things are. . . I think that it’s a tough time to write. There’s not much of a sense of where do we go next. I think we finally hit the point of, “What do we have left to believe in?” I think we’re starting to realize that the world is going to be a series of conflicts and problems without answer, as it has been for a long time. But we at least had some optimism. There’s not a sense of where do we go next as a people. I was trying to get as expansive with my book as possible. . . how much can we bring through the eye of this needle? How much heart can we reinvest in the system? Because people are in need of something inspiring. That’s not commerce only, or capital only. I think anyone writing with with vulnerability or a willingness to question themselves, and to get honest, is someone we need right now. Someone who can get true to their condition, who has a life force, who has passion. »

– Scott McHale