BEAUTY & VIOLENCE: PRACTICAL EFFECTS FOR A NEW ERA

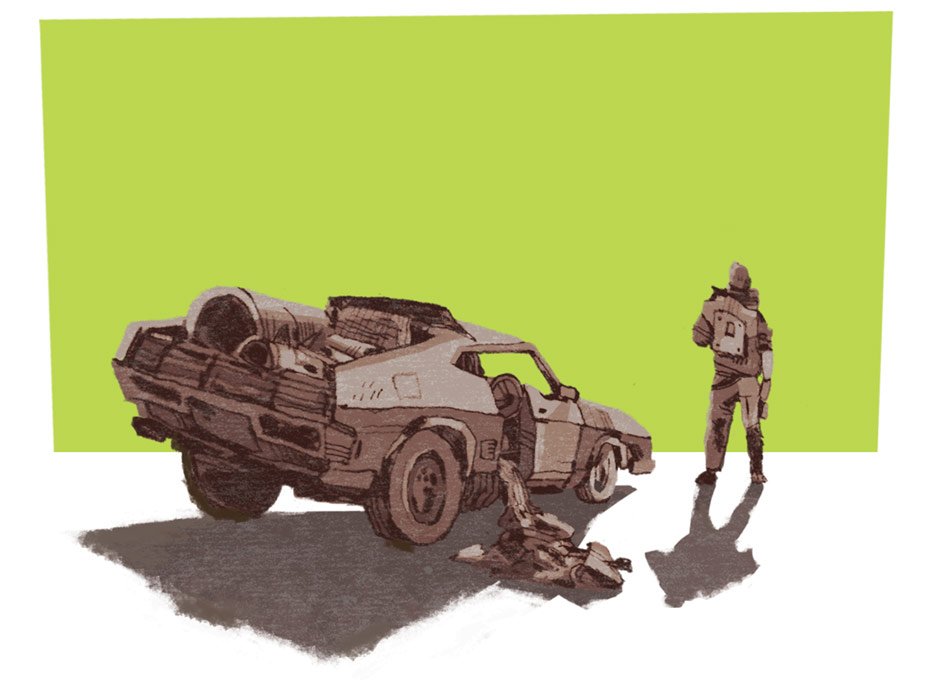

Film is about the representation, or perhaps, misrepresentation of reality. What is reality? How can the fantastic meld with the surreal with hyper-reality…with…well, that’s for Film Studies 101. Since the advent of the film age, special effects have been used to heighten our awareness of the goings-on within the narrative, and to bring viewers enveloped within the realm of the fantastic. Practical effects—those effects built in creature shops and design workshops around the world. In short, a practical effect is a special effect produced without computer-generated imagery or other post-production techniques. In recent memory, the deluge of science fiction films have relied heavily on computer generated imagery to construct worlds fantastic, often at the stake of authenticity (Ahem, Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace…). The phrase “the uncanny valley” is a hypothesis in the field of aesthetics–and manifests itself most recently in robotics—which ascertains that when features look and move almost, but not exactly, like natural beings, it causes a response of disgust (and sometimes fear) among some observers. A similar sensation can occur when one is barraged with an over abundance of computer generated images. RE: it is off-putting, inauthentic and a cardinal sin of film–uninteresting. Speaking with Edgar Wright (of Hot Fuzz and Shaun of the Dead fame) following an early Los Angeles screening, Mad Max: Fury Road director George Miller said, “You couldn’t make this as a CG movie.”

CG, of course, is a necessarily evil, though not to create an impossible scenario, but more to aid in the vision, as Miller describes in the film’s production notes saying, “Fury Road was an opportunity to more fully realize its scope and energy with all the latest technologies. We could put our cameras where they wouldn’t go in the past, and weave them through the armada with the wonderful Edge Arm system. If there was a fight on a vehicle, we could put wires on the actors then erase them with CGI.

When you see Max hanging upside-down between two vehicles, that was Tom Hardy. When Furiosa is hanging onto him, that was Charlize Theron hanging onto Tom. And when you see Nux climbing onto the front of a vehicle, that was Nicholas Hoult.” Granted, a lot of the work was done by stunt performers, but that doesn’t dull their effectiveness. Miller reminisces on one scene where characters swing in the air from giant poles affixed to moving battle-cars, showing just how much practical effects matter to contemporary audiences, engorged on CGI, and, most likely, doubting the reality of anything they see anymore—numbed to overwhelming false grandeur.

Will audiences even go home asking themselves, “How’d they pull that off?” In the case of the sequence mentioned above, after months of failure leading to the thought that it may have to be done digitally, stunt coordinator Guy Norris and his team (which included as many as 150 stunt performers at once) hit pay dirt with a system that included poles reaching as high as thirty feet, counter-weighted with an engine block at the base, positioned at the fulcrum point, which could be adjusted for different performers and moves. The device allowed the “Polecats” to glide through the air by coordinating their moves with the stunt team positioned on the vehicle, pushing and pulling the weighted block for leverage. Those “Polecats,” by the way, were assembled by Cirque du Soleil performer Stephen Bland. Will that matter to you while you’re watching? Will that sense of realism make for a more visceral experience? Where we may feel the impact is in the performances. Actor Nicholas Hoult, who plays the character Nux in Fury Road notes, “There’s nothing like feeling the rumble of a big V-8 engine underneath you and hearing trucks as they roar past with bombs going off and people being flung around on poles.” Meanwhile Tom Hardy, who plays the titular Max Rockatansky adds, “If you think a stunt is too extreme, or an explosion too spectacular, I promise you that it was there… I saw it.”

It is important to distinguish Mad Max amongst its peers—George Miller has always used a plethora of complex practical effects to describe his dystopia, and the results have paid off in spades with a gorgeous, complex series of action sequences that perfectly balance the narrative—in fact, they create plot structure almost more than the dialogue ever did in any of the Mad Max films. While epics like Star Wars, Star Trek and others have looked to heavy CGI to attempt to maintain relevance or undergo a kind of revamping, Mad Max has remained a fully committed practical effects universe. It’s all the better for it, and hopefully the craftsmanship and imagination that has long gone into effects-making returns triumphant to our screens. »

– Rachael Haigh