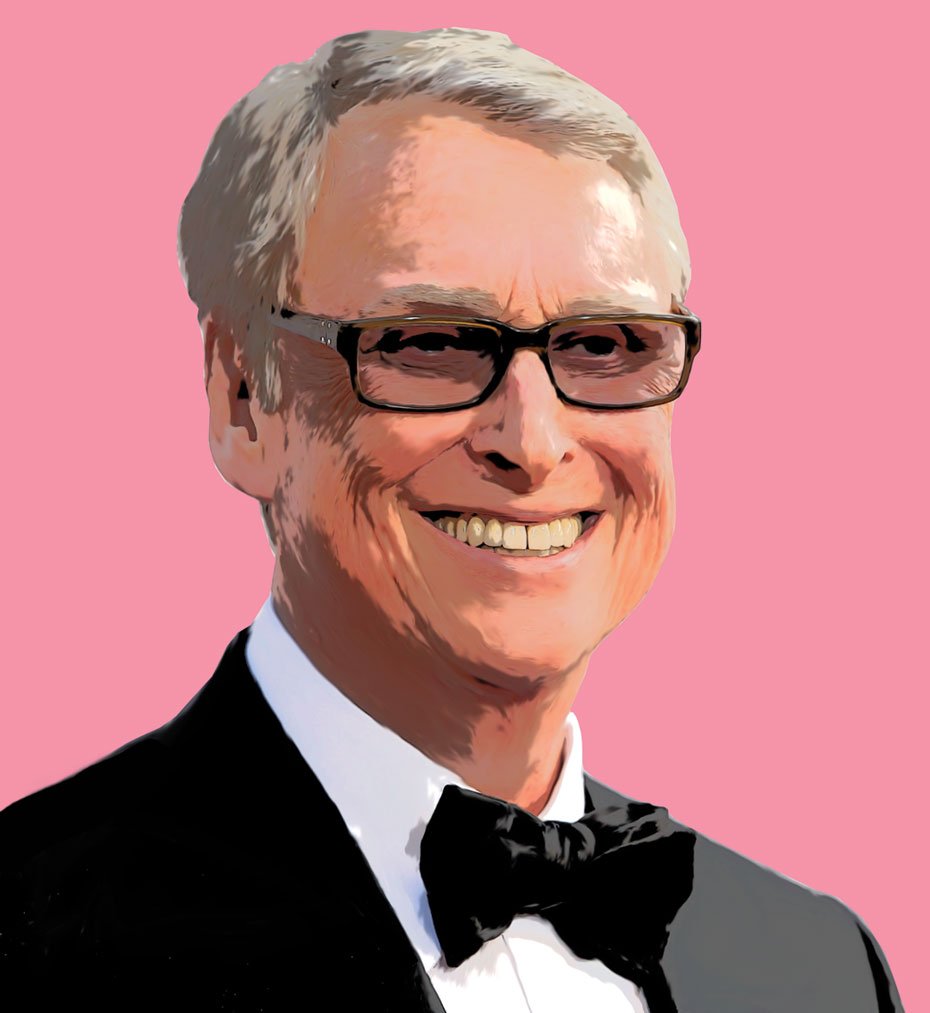

THE FUNDAMENTALLY INCONSOLABLE: REMEMBERING MIKE NICHOLS

Mike Nichols was a master of self-satire; he was a man of wealth and education; and one of connections, whose best targets were those who had wealth, education, and connections. Born Michael Igor Pechowski in the waning days of Weimar Berlin, Nichols was a man generous of both spirit and wit. His career encompasses an entire era of stage and screen, beginning with his early days in improv comedy where he met creative and comedy partner Elaine May. Nichols and May would go on to be wildly successful, doing shows in nightclubs and television, eventually landing on Broadway with An Evening with Mike Nichols and Elaine May. After May and Nichols called their duo quits in 1962, he launched his storied stage, film and television métier.

Nichols worked with a steady stream of luminaries, and directed some of the greatest performers of the mid twentieth century, such as Julie Christie, Lillian Gish, George C. Scott, and Richard Dreyfuss on Broadway. Nichols had a healthy Off Broadway career as well, directing Steve Martin and Robin Williams as Vladimir and Estragon in Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, and he directed Meryl Streep, Natalie Portman, Christopher Walken, John Goodman, and Kevin Kline in Chekhov’s The Seagull. He ushered young actors like Jack Nicholson, Harrison Ford, Julia Roberts, and Candice Bergen into stardom, and veteran actors like Anne Bancroft and Gene Hackman all clamored to work with him. When Nichols directed Burton and Taylor in Virginia Woolf, they were the biggest stars in the world. All in all, Nichols coaxed remarkable performances out of his actors, leading approximately sixteen of them to Oscar nominations or wins. Nichols’ propensity to garner nuanced performances lent him the reputation of being a director who creates films purely as vehicles for his actors, many of said films are relinquished of any trace of his particular artistic signature.

Unlike other celebrity filmmakers—two contemporaries include Woody Allen and Martin Scorsese—Nichols was never known as an auteur. He did not create an overtly recognizable visual style or a distinct aesthetic imprint; his thematic interests were disparate. To that end, however, romantic narratives were his main vehicle, particularly narratives regarding the institution of marriage. Nichols was a svengali of domestic tension, deftly setting up astringent connubial dramas. One particular talent was Nichols’ examination of marriage: from the nascent, as in Barefoot in the Park; to the suddenly crumbling, as in his adaptation of Heartburn (1986), Nora Ephron’s novel about a wife deceived by her husband; to the decayed and intolerably brittle, as in Virginia Woolf.

Nichols scrutinized courtship rituals in films like Carnal Knowledge, which follows the sexual education of two men (Art Garfunkel and Jack Nicholson), and Closer, adapted from Patrick Marber’s play about power dynamics and seduction in the internet age; in adaptations of plays like The Real Thing, Tom Stoppard’s disinterring of the meaning of love. He found equally flush material in homosexual relationships, as epitomized in The Birdcage, whose script was adapted with long time comedy partner Elaine May.

Perhaps the film that carved out Nichols’ legend is his 1967 film The Graduate. Nichols’ second foray into directing after Virginia Woolf, the titular character became a bellwether for how the baby boomer generation dealt with at the uncertainty of the changing, post-war world of their parents. Never once did it venture into social commentary of the time like civil rights, or Vietnam. It was a meditation on confusion and scorn, gifting Nichols his lone directing Oscar. Nichols’ background in improvisational, satirical comedy informed many of his films, which often started out as comedies and ended up as acerbic ruminations on American relationships. Directing material by playwrights, screenwriters, and novelists, his dialogue and staging seem edgy but aren’t rough; they’re refined but not callous. His films have the common denominator of being commercially accessible while retaining their intelligence and attention to detail. »

– Rachael Haigh