Paulann Petersen

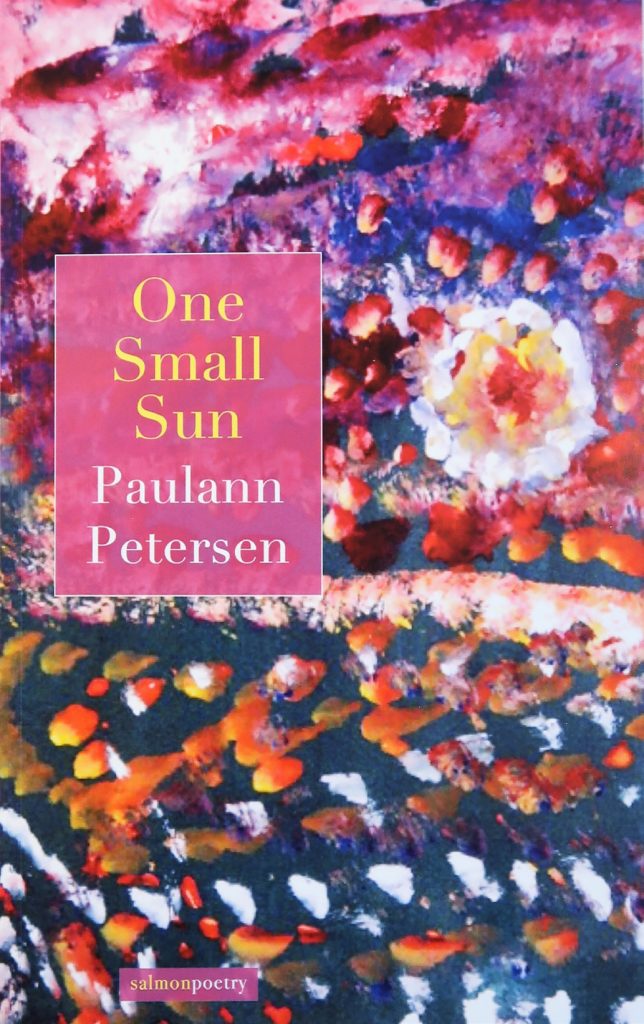

From Franklin High School graduate to Oregon Poet Laureate, Paulann Petersen has lived the life many aspire to at an early age, but give up in favor of other pursuits. Her poetry, lyrical and emotional, powerfully speaks to that part of us that is often checked-out. More now than ever, we need poetry that both examines and interrogates our past to make sense out of our present. I caught up with Paulann Petersen to discuss her latest collection One Small Sun (2019 Salmon Poetry), where she invites the reader into her memories through a collection of poems that in her own words, “have a story to tell”. In person, Paulann Petersen is as a warm and accessible as her writing is.

ELEVEN: When did you start writing?

Paulann Petersen: In high school, I won an award from a Portland magazine for young poets at that point. I don’t think that I took that all that seriously, or my writing of poetry seriously, but I was always an avid reader, and very moved by prose and poetry. As a young adult, by that time living in Klamath Falls, I was reading a lot of the Saturday Review and I encountered the poetry of contemporary poets. And they just knocked me out. They were so different than the poetry that I had read in college or high school. Which was usually anthologized and from an earlier era. Here were poems that for me seemed like the ink was barely dry. I just said to myself, I want to do that. So I started writing on my own — No writers group, no MFA program, no classes. I just started writing. Then after a while, I learned that you could send poems out to magazines. I started sending some poems out, and I had some accepted and I kept writing, and got more poems accepted and published in magazines and journals.

11: What do you think of MFA programs? Can poetry truly be taught in a classroom?

PP: People argue about what MFA programs do. There are wonderful poets that come out of those programs. But there are different opinions about them. When I was at Stanford, Stanley Kunitz was one of the poets who visited and he said that he questioned them because he thought a lot of them were like “hothouse flowers”. I don’t know, that’s kind of harsh. I could just begin to name off a huge list of people….

11: Can you tell me about your new book, One Small Sun?

PP: This book, One Small Sun, is a real departure for me. Because this book is filled with longer poems. I call them “poems with stories to tell”. I wouldn’t call them exactly narrative poems because I think that there is a fair amount of lyricism in them. In this collection there are poems that were brand new. There are also poems in this book that are older, much older. My earlier books have shorter more intensely lyric poems. But all through my working life as a poet, I have occasionally written poems that have narrative strands in them. And I worked on them very hard, and gratefully, but set them aside. Then about three or four years ago, I came across one of these poems that I had set aside. I read it and it just struck me, there is something resonating here. I started fishing out, from the archives as it were, some of these earlier poems in type and genre and seeing strengths in them. I came to the point where I sort of set myself a task…I challenged myself to gather these poems together to write a number of new poems in this genre and to shape a book out of them.

11: One of those poems that struck me was Belated, which goes into a certain part of American history that is mostly left out of the text books. Can you speak about that a bit?

PP: The title alludes to the fact that when I knew her, when we were both in high school, it wan not talked about. It’s not only that the Japanese Americans (not each and every one of them but as a whole) didn’t talk about this experience, even within the families. They just didn’t talk about it. Also, I remember learning nothing about the Japanese internment camps in high school social studies. There’s a wonderful book by Lawson Inata, who was my mentor who was the Oregon Poet Laureate before me. He has a wonderful book called Only What We Could Carry, because that’s what the families were allowed to take with them to the camps, (when I say wonderful, it’s heartbreaking too). That was the definitive book on the camps and the experience of Japanese Americans during World War II.

11: What advice would you give a young poet or writer, or any artist for that matter, who is at odds on whether to pursue their creative impulse with a career in art, or work in a cubicle somewhere?

PP: “Poetry speaks the language of us at our best. When we are the most creative, attentive, responsive. Now we are spoken

to in languages of commerce, conversation. Most of the time, the language we are spoken to when someone is trying to get some information across to us. Maybe someone is trying to get our vote. Maybe someone is trying to persuade us in one way or another, are just impart some information to us. But when a poem is good, when a poem is really working, it is speaking to that part of us that we are at our best. Where we are creative, attentive, responsive. So that’s a wonderful endeavor, to work in that realm. That’s what art does. When we write, I think, we write to create ourselves. To discover moment to moment

who we are, who we are becoming. I believe all artists, of all

genres are doing that. To turn your back at that — to not both

acknowledge and give yourself, or at least a big part of yourself

to that I think is cutting yourself short. Denying that part of

you that is the most creative, attentive, responsive. You are

snubbing it. turning your back on it. I think that we are much

better, in terms of to ourselves, to others around us, to the

whole world if we are attending to that. If we are listening to

that, responding to that. So I would say: Write, write, write.

Those of you who have that predilection. Say yes to it. Say

a thousand yeses to it! And to the musicians, to the dancers,

to the sculptors, to the painters. Say yes, say yes. That’s a

wonderful part of us, and not a part that we want blunted, or

muted, or extinguished.

Belated

Janice Nakata, May Fete Queen, Honor Roll girl, I’m glad I was once your sister—if only in a high school club playing 1950’s grownup with our bids and blackballs and pledge week, our pale organza formals, our long white gloves. Janice with skin the color spun from wild honey, did you wince at me? —the tall thing one blotched by moles and imperfection, admiring in silence your sweet-spoken ways, your darkest eyes that me our eyes with only kindness.

I must have thought we’d all grown up much like me, with a father exempt from the army because he worked in the shipyards, a father left at home to weld, sealing those giant hulls bound for Pacific seas—a daddy free to build his daughter a wooden stepstool that exact size so she could reach the bathroom sink to brush her teeth, a dad who could drive her to see grandparents in their gabled house just across our tree-shaded city.

Janice Nakata, Beautiful Sister, I ask you now what I did not know to ask you then. Tell me.

Where—in which makeshift barrack shadowed by high barbed wire—did we imprison your family during the war?

Paulann Petersen