Sophia Shalmiyev

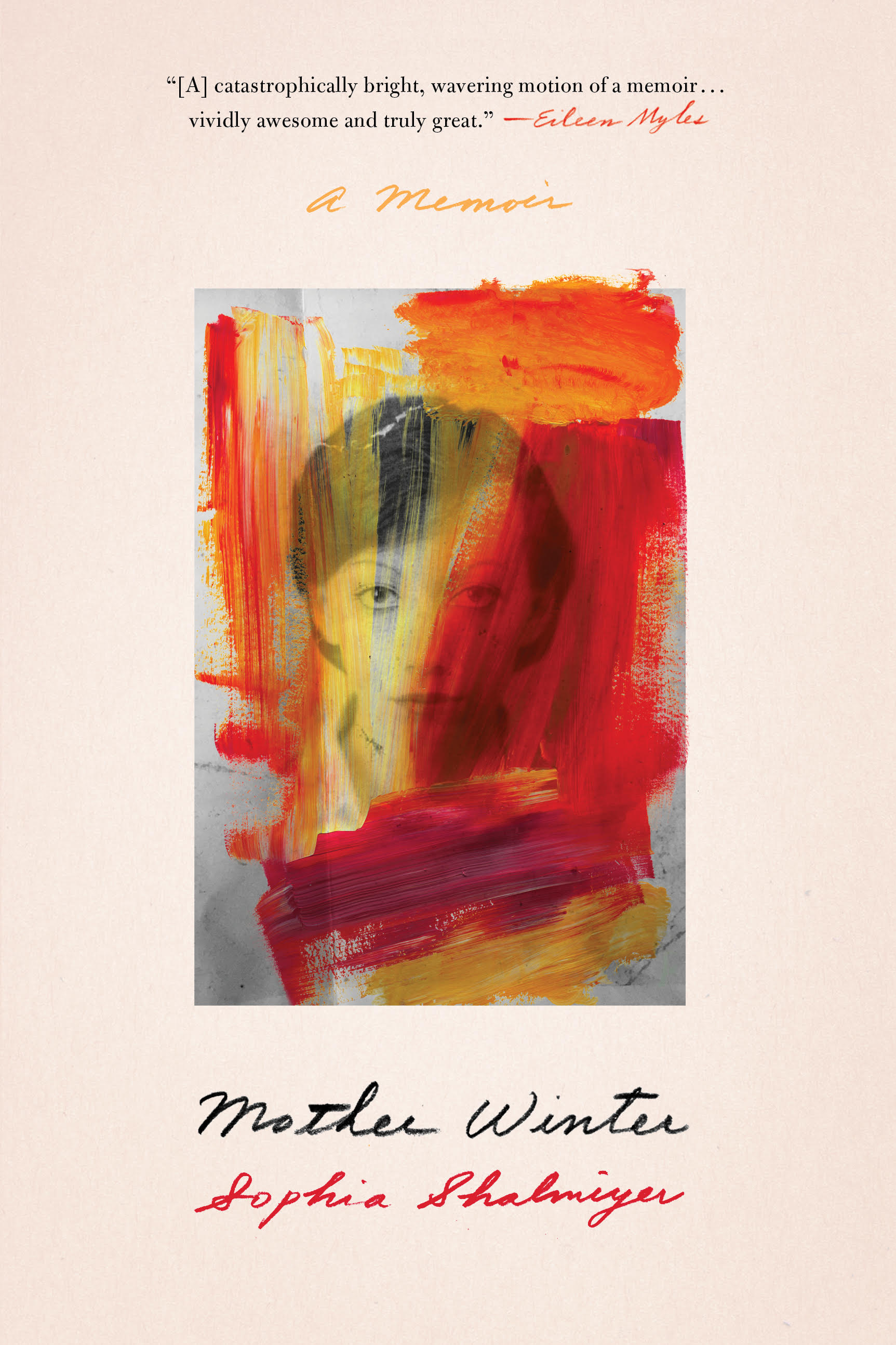

As a child of 1980s Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg), Sophia Shalmiyev lived in a communal flat with her young father, who was “dependable as the dawn” while longing for her absent mother, who she describes in her memoir Mother Winter as a “mythical beached mermaid swimming home from the bar in the dark.” Shalmiyev tells her life’s story in lyrical vignettes that depict a mother she loved deeply but was forbidden to see, close to her heart but completely lost, deemed unfit, and cast off because of her alcoholic lifestyle.

Mother Winter is a heartbreakingly honest account of growing up in the former Soviet Union. While the memoir marks a debut for Shalmiyev, it reads as though from a seasoned writer and has already been featured as a staff pick by the Paris Review and made The Millions’ list of Most Anticipated Books of 2019.

I met up with Shalmiyev to discuss her upbringing as detailed in Mother Winter, her mother and own motherhood, and her interests in numerology and bunnies. The author launches Mother Winter at Powell’s City of Book on Tuesday, Feb. 12, with an after-party at Mother Foucault’s Bookshop.

ELEVEN: So how did this book come to be?

Sophia Shalmiyev: While I was doing my second round of graduate school, I sort of went into this wormhole. I realized I had been parenting as though I’m holding my breath. I had been parenting from this enormous intense lack, and I had been doing everything in such a solitary way. I had been doing everything myself, and I had been so hard on myself that my body was breaking down, and everything was breaking down. The only thing that I could do was make art about it. I wanted to write a feminist book. Specifically a book that was not in the feminist section. It’s a book that you just pick up as pure literature, but it is straightforwardly feminist without any apologies. That was my initial interest, but as I was holding this tiny four-month-old baby that I was bringing to workshops and class with me I think that it all seeped in. Who was I as a woman to this girl? What was I giving her? I felt so depleted and didn’t know where that came from.

ELEVEN: There’s a scene in the book where you have to decide how much of a portion of food you can split with your father, but at the same time, you were going to boarding school. Can you explain this dichotomy? That would probably never happen here.

SS: Totally. That’s a foreign concept; no pun intended. My dad did have to work really hard and pull strings, but boarding school was free as is most education in Russia, but who gets into what has a lot to do with connections. A boarding school in Russia is different also because you get to come home on weekends, and the boarding school could also be a day school for people. My boarding school was as far as Astoria would be from here. My dad got me into it after he tried to get me into a Hindu boarding school…the idea was that everybody was trying to get their children to learn a foreign language or study foreign cultures so maybe they could get out and be diplomats or translators. The feeling at the time was that if things collapsed, we’d need that as a backup, and the exotic West was just calling to everybody. Anyway, I didn’t get into the Hindu one, or the Japanese one. I didn’t get into any of them, and this was my dad’s last-ditch effort. In this school, they started to teach you really terrible English, like at a second grade level. I only lasted there until fifth grade, and by the time I got here, I could say something like, “Breakfast is at half past six” in a bad British accent.

ELEVEN: You write in the book that “we all have a propensity for false pattern recognition, to look for meaning, a belief system when my story is too anxious of a box to contain us — a story that can signify a completeness we have only felt in the darkness of our mother.” What made you go back to Russia to find her?

SS: Children who have been traumatized and displaced, like refugee children, have the resignation syndrome. What I wanted to say about having to look for my mom is that I think that the way trauma works, neurologically in your brain, the way a human being disassociates…that is how I made the decision. There was a series of times where I was really checked out and really not in my body. I did not have self-agency a lot of times. It didn’t feel like it was really up to me.

It felt like enough seemingly normal people in my life — nice, sweet, adjusted American people — have asked me the question: “Are you spending the holidays with your mom?” And so many times you either choose to not answer the question, or come up with something. You start to realize to yourself how crazy it is. I had so many years of pretending to be brave or pretending to be OK with it where at some point it was all just sinking me. I had a best friend and a boyfriend both of whom were really just interested in this thing happening. In a way, I just kind of gave in or went limp before my destiny, as it were. I didn’t feel like I was making the decision; I feel like I was just really tired of pretending it wasn’t happening. So to go back to see her, yeah, I was definitely numb throughout the whole process. It didn’t help me at all, in the end.

ELEVEN: Can you talk about how numerology relates to Russian culture? You go into it a bit in the beginning of the book, especially the number four.

SS: In Eastern Orthodox Church it is important, but the reason it became important to me is that while I was in Hebrew Academy, we learned the name for God is this unutterable four-letter word. It’s unutterable for many reasons, the first being that you’re not supposed to take the Lord’s name in vain. There’s a way you say the word for God when you’re just talking conversationally, and then you have it for prayer. But then, there’s another word that’s not translatable and has four letters. It’s a multi-syllabic word that’s unpronounceable because if you try to pronounce all of it, you’re gasping for air. The idea is that every breath you take, God is with you. It’s a very old thing that people are now disputing and lots of rabbinical scholars are taking a look at. To me, it appealed because I when I kind of came to…figure out where I’m at and what’s going on in my life toward the end of Yeshiva, and hearing that said about an invisible, unutterable, worshipful presence and my Mom, this absent unspoken about, unutterable person, it just stuck with me forever.

I think superstitions also work to organize unmanageable lives in Russian culture. I look for patterns in life, so I became interested in stability. The number four is a vehicle to organize some your thoughts and family history over time. I listen for it everywhere. It was a great way to corral the unmanageable and arrange things. The book has its own logic and numerology is one way to do it, but there are other animalistic, occult ways. All those things go together for me.

ELEVEN: Is there a specific animal that is meaningful to you?

SS: Bunnies, horses, rhinos. I talk toward the end how a bunny mothers, how there are so many different kinds of mothers in the mammalian kingdom and how there are many different mothers in our culture. The way the bunny mother works is that she’ll give birth to this litter, she’ll make a hole for them, a burrow. Then, she will come to them only when her teets are so full, as full as bursting grapes, and she’ll lay over the hole, feed them and then run away again because she doesn’t want any predators to see them. That reminded me of my Mom: just doing the bare minimum, but maybe she was protecting me from her, being both the predator and the nurturer.